Scotland is hame tae a vast rowth o tales frae the oral tradition which nou survive in prent. The feck o these wir hairstit frae the Traiveller clans wha wir whiles kent as cairds, tinkers or Scottish Gypsies. The Traivellin fowk in Scotland are said tae be a distinct group frae the Romani peoples, tho they share some common aspecks in tradition an culture wi shared wirds in the Cant and Romany languages sic as habin (food) and vardo (caravan). Wirds o Cant origin hae been takken tent o as pairt o the Scots vocabulary syne the advent o the earliest Scots dictionaries. Traivelin fowk in the West Hielans wir aince said tae hae spoken a distinctive Gaelic.

The Traivellers in Scotland wir famed as pipers, ballad singers an seanachies (meanin storytellers, originally frae Gaelic). The braw wirk cairried oot bi folklorists in the latter hauf o the 20th century has made siccar a rowth o tales frae the traiveller tradition, mony o which hae been translatit intae prent frae ther original recordins. This has meant in mony cases – whaur the editor has held true tae the vyce o the narrator – that the Scots leid an idiom haes been reteened tae guid effect.

Amang the mony braw seanachies whase wirk wis owerset intae prent in modren times are Duncan Williamson, Stanley Robertson, Betsey Whyte an the Stewart faimilies o Perthshire. Amang the mony buiks an imprentit collections are ‘A Thorn in the king’s foot’ bi Duncan and Linda Williamson (Penguin, 1987. Shelfmark: HP2.87.2890), ‘Till doomsday in the afternoon the folklore of a family of Scots Travellers, the Stewarts of Blairgowrie’ bi Ewan MacColl an Peggy Seeger (Manchester University Press,1986. Shelfmark: HP2.88.6739) an ‘Reek roon a camp fire’ bi Stanley Robertson (Birlinn, 2009. Shelfmark: PB5.209.1325/3).

Lear mair aboot Traiveller tales

Storytellin in Scotland comes frae a timeless an borderless tradition. Mony o the stories that hae come doon throu the Traivellers hae been identified bi folklorists as haein versions in a wheen o nations an amang peoples oot-throu the warld. The types an motifs o stories are generally classified in the Aarne-Thompson index whaur practically aw stories frae the oral tradition are shawn tae be variations on general themes.

The pouer o this tradition wis recognised in the 1549 imprent ‘The Complaynt of Scotland’, a polemic scrievit bi Robert Wedderburn at the time o Henry VIII’s attempt tae aggressively impose an alliance atween England an Scotland. Wedderburn ettles tae shaw the strynth o Scotland’s cultural heritage. Amang ither exaumples he references twa stories – ‘Tam Lin’ an ‘The Red Etin’ – which hae survived tae the present throu the oral tradition an in buiks sic as Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’ an in Duncan an Linda Williamson’s ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’. (First imprentit 1987). A ballad version o Tam Lin, ‘Thomas the Rhymer and Queen of Elfland’ alsae appears in the ballad collection o Anna Gordon.

In the preface an introduction tae ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ some insicht is gien anent baith the language an provenance o Duncan’s stories. Linda Williamson, an American folklorist an storyteller wha wis merrit tae the late Duncan Williamson, scrieves hou Duncan’s speech wis a mixter o baith English an Scots. In mony weys this is reflectit in the text an is exponed bi the circumstances o Duncan’s early life on Loch Fyneside in Argyllshire whaur his spoken leid wis said tae be ‘Highland English’. His Scots tung wis later acquired whan he traivellt amang the Lawlands an tae the nor-east an sooth o Scotland.

Fir conventions in scrievit Scots, Linda refers tae the ‘Manual of Modern Scots’, a 1921 imprent bi academics William Grant an James Main Dixon. This ettled tae interpret scrievit an spoken Scots fir the modren scholart particularly fir students owerseas wha had less o a kennin o the Scots tung. In Hamish Henderson’s introduction a guid accoont is gien o the folklorist’s discovery in the 1950s o the rowth o stories that bade amang the Traivellin fowk. Frae Jeannie Robertson’s ceilidh-hoose in Aiberdeen an amang the berry fields o Blairgowrie, stories were hairstit fir the common-weel and are noo keepit in the archives o the School of Scottish Studies at the University o Edinbrugh.

‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ is a byous collection o twinty three tales, scrievit doun bi Linda as Duncan wid hae tauld them. Ither buiks bi Duncan Williamson include ‘Broonie, Silkies and Fairies’, ‘Fireside Tales of the Traveller Children’ an ‘Horsieman’.

‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ (first imprentit bi Manchester University Press, 1986) bi Ewan MacColl an Peggy Seeger is taen frae a series o recordins o the Stewarts o Blairgowrie faimily atween 1962 an 1979. Throu music an folklore, Ewan MacColl an Peggy Seeger are kent as gien a muckle heize tae the fowk traditions oot-throu Britain an America. The introduction gies some backgrun tae the Traivellers’ wey o life as weel as gien a glossary o cant wirds as yaised bi Traivellin fowk. Transcribed frae the tellins o the Stewarts, the buik alsae kythes a wheen o stories, riddles, bairn rhymes an sangs. The stories are a mixter o wonder-tales frae the deep wall o tradition as weel as mair recent anecdotal (though aften wildly extravagant) or humorous tales. The riddles recordit in MacColl an Seeger’s collection are a mixter o baith the innocent an racy. The sangs include ancient ballads, popular folk-sangs, bothy ballads an bawdy sangs frae the ribaldry o the Scots tradition. Ther are alsae ‘mak ye ups’, sangs wi kent Traiveller authorship or frae livin memory.

The seanachie’s tales aften follae a pattern whaur a journey is undertaen an privations are owercome, aftimes throu some supernatural agency. A lesson is usually learned an ther is some reward or forfeit at the end o the tale. ‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ gies types an motifs frae the Aarne-Thompson index tae maist o its folktales. The collection is fouthie wi Scots wirds an expressions an shares a common tale (as micht be expectit) wi Duncan Williamson’s ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’. This is the story cried ‘The Cripple in the Churchyard’ which in Williamson’s buik is cawed ‘The Tailor and the Skeleton’. Alsae common tae mony Traivellers collections are tales o a protagonist cried Jack. Jack is a kenpseckle figure, aften gleg an canny aneth his ootwardly blate appearance, wha wins throu in the end. While ‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ offers ane Jack tale, ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ offers several.

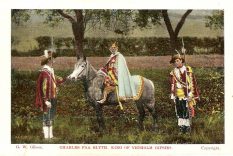

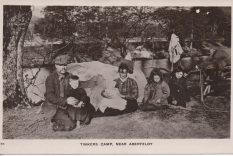

Sharin mair than ane tale in common wi ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ is Stanley Robertson’s magical ‘Reek Roon A Camp Fire: A Collection of Ancient Tales’. Bidin in the memory o Stanley as a loon, the tales are embeddit in the seasonal ritual o nor-east Traivellers as they settle then muive camps, frae pearl-fishin at Deeside tae the berry fields bi Lumphanan an on tae the flax hairst at Alford. The reader is gien a deek intae the intimate circle o ‘the glimmer’ (fireside) as a cast o worthies pass through tae tell their tales, beirin names like Meldrum Brews, Madame Cabanya, Maisie Moor Loch an Auld Gruer. Ther are a wheen o Jack tales, alangside ugsome stories o the calibre o ‘The Tattiebogle’, an antrin tale o a scarecraw made frae human body pairts. Ther is the tellin o ‘The Gaberlunzie King’, a traditional tale whiles kent as ‘The Guid Man o Balengeich’ which is said tae be haundit doon frae the times o James V of Scotland whan the king wid traivel aroond in the guise o a beggar-man.

The language o ‘Reek Roon a Camp Fire’ is a rowthie an powerful mellin o Cant an Doric. In the glossary, Stanley Robertson shaws the provenance o his wirds tae alsae be frae Romany, Gaelic an Scots origins, makkin a distinction atween Doric an Scots. Amang the Cant wirds are:

. cane – house

. hantel – people

. monteclara – water

Mony collections o Traivellers’ Tales hae ‘Burker’ stories, rootit in the murderous exploits o Burke and Hare wha preyed on live human specimens as weel as cadavers fir supply tae the Edinbrugh anatomy schuil in the 1820s. The memory o Burke an Hare lours wi menace in the collective Traivellers’ memory an the final piece in the buik. The Kenchins’ Ceilidh is a bairns’ re-enactment frae this tradition. Stanley Robertson’s life is alsae kythed alangside the tales. Frae his wark as a filleter in Aiberdeen (a warld explored in his memoir ‘Fish Hooses’) tae becomin a weel-kent ballad singer an seanachie, these skeels wid tak him tae festivals oot-throu Europe, Britain an North America an lead tae him bein recognised as a teacher an cultural ambassador tae the Traivellin peoples o Scotland.

Scotland is home to a vast wealth of tales from the oral tradition which now survive in print. The majority of these were collected from Travelling families variously known as cairds, tinkers or Scottish Gypsies. The Travelling people in Scotland are said to be a distinct group from the Romani peoples, though they share some common aspects in tradition and culture including shared words in the Cant and Romany languages such as habin (food) and vardo (caravan). Words of Cant origin have been acknowledged as part of the Scots vocabulary since the advent of the earliest Scots dictionaries Travelling people in the West Highlands were once said to have spoken a distinctive Gaelic.

The Travellers in Scotland were famed as pipers, ballad singers and seanachies (meaning storytellers, originally from Gaelic). The great work carried out by folklorists in the latter half of the 20th century has secured a wealth of tales from the Traveller tradition, many of which have been translated into print from their original recordings. This has meant in many cases – where the editor has held true to the voice of the narrator – that the Scots language and idiom has been retained to good effect.

Among the many fine storytellers whose work was translated into print in modern times are Duncan Williamson (1928-2007), Stanley Robertson (1940-2009), Betsey Whyte (b. 1919) and the Stewart families of Perthshire. Among the many books and published collections are ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ by Duncan and Linda Williamson (Penguin, 1987. Shelfmark: HP2.87.2890), ‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ by Ewan MacColl an Peggy Seeger (Manchester University Press,1986. Shelfmark: HP2.88.6739) and ‘Reek Roon a Camp Fire’ by Stanley Robertson (Birlinn, 2009. Shelfmark: PB5.209.1325/3).

Learn more about Traiveller tales

Storytelling in Scotland comes from a timeless and borderless tradition. Many of the stories that have come down through the Travellers have been identified by folklorists as having versions in a number countries and among peoples throughout the world. The types and motifs of stories are generally classified in the Aarne-Thompson index where practically all stories from the oral tradition are shown to be variations on general themes.

The power of this tradition was recognised in the 1549 publication ‘The Complaynt of Scotland’, a polemic written by Robert Wedderburn at the time of Henry VIII’s attempt to aggressively impose an alliance between England and Scotland. Wedderburn strives to show the strength of Scotland’s cultural heritage. Among other examples he references two stories – ‘Tam Lin’ and ‘The Red Etin’ – which have survived to the present through the oral tradition and in books such as Robert Chambers’ ‘Popular Rhymes of Scotland’ and in Duncan and Linda Williamson’s ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ (first published in 1987). A ballad version of Tam Lin, ‘Thomas the Rhymer and Queen of Elfland’ also appears in the ballad collection of Anna Gordon.

In the preface and introduction to ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ some insight is given to both the language and provenance of Duncan’s stories. Written by Linda Williamson, an American folklorist and storyteller who was married to Duncan, she writes how Duncan’s speech was a mixture of both English and Scots. In many ways this is reflected in the text and is explained by the circumstances of Duncan’s early life on Loch Fyneside in Argyllshire where his spoken language was said to be ‘Highland English’. His Scots tongue was acquired later when he travelled among the Lowlands and in the north-east and south of Scotland.

For conventions in written Scots Linda refers to the ‘Manual of Modern Scots’, a 1921 publication by academics William Grant an James Main Dixon. This book set out to interpret written and spoken Scots for the modern scholar, particularly for students abroad who were less familiar with Scots tongue. In Hamish Henderson’s introduction a good account is given of the folklorist’s discovery in the 1950s of the wealth of stories that survived among the Travelling people. From Jeannie Robertson’s ceilidh-house in Aberdeen and among the berry fields of Blairgowrie, these stories were collected for posterity and are now held in the archives of the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ is a wondrous collection of twenty three tales, written down by Linda as Duncan would have told them. Other books by Duncan Williamson include ‘Broonie, Silkies and Fairies’, ‘Fireside Tales of the Traveller Children’ and ‘Horsieman’.

‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ (first published by Manchester University Press, 1986) by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger is taken from a series of recordings of the Stewarts of Blairgowrie family between 1962 and 1979. Through music and folklore, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger have been recognised as great promoters of folk traditions throughout Britain and America. The introduction gives some background to the Travellers’ way of life as well as providing a glossary of cant words as used by the Travelling people. Transcribed from the storytelling of the Stewarts, the book also features a numbers of stories, riddles, children’s rhymes and songs. The stories are a mixture of wonder-tales from the deep well of tradition as well as more recent anecdotal (though often wildly extravagant) or humorous tales. The riddles recorded in MacColl an Seeger’s collection are a mixture of both the innocent an racy, while the songs include ancient ballads, popular folk-songs, bothy ballads and bawdy songs from the ribaldry of the Scots tradition. There are also ‘mak ye ups’, songs with known Traveller authorship or from living memory.

The seanachie’s tales often follow a pattern where a journey is undertaken and privations are overcome, often through some supernatural agency. A lesson is usually learned and there is some reward or forfeit at the end of the tale. ‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ gives types and motifs from the Aarne-Thompson index to most of its folktales. The collection is abundant in Scots words and expressions and shares a common tale (as might be expected) with Duncan Williamson’s ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’. For example, there is the story called ‘The Cripple in the Churchyard’, which in Williamson’s book is called ‘The Tailor and the Skeleton’. Also common to many Travellers’ collections are tales of a protagonist named Jack. Jack is a familiar figure, often skilful and shrewd beneath his outwardly modest appearance, who wins through in the end. ‘Till Doomsday in the Afternoon’ offers one Jack tale, while ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ offers several.

Sharing more than one tale in common with ‘A Thorn in the King’s Foot’ is Stanley Robertson’s magical ‘Reek Roon A Camp Fire: A Collection of Ancient Tales’. Dwelling in the memory of Stanley as a boy, the tales are embedded in the seasonal ritual of north-east Travellers as they settle then move camps. From pearl-fishing at Deeside to the berry fields by Lumphanan and on to the flax harvest at Alford. The reader is given a glimpse into the intimate circle of ‘the glimmer’ (fireside) as a cast of characters bearing names like Meldrum Brews, Madame Cabanya, Maisie Moor Loch and Auld Grue, pass through to tell their tales. There are a number of Jack tales alongside gruesome stories of the calibre of ‘The Tattiebogle’, an eerie tale of a scarecrow made from human body parts. There is the telling of ‘The Gaberlunzie King’, a traditional tale sometimes known as ‘The Guid Man o Balengeich’. This tale is said to be handed down from the times of James V of Scotland when the king would travel around disguised as a beggar.

The language of ‘Reek Roon a Camp Fire’ is a rich and powerfu mixture of Cant an Doric. In the glossary, Stanley Robertson shows the provenance of his words to also be from Romany, Gaelic and Scots origins, making a distinction between Doric an Scots. Cant words include:

. cane – house

. hantel – people

. monteclara – water

Many collections of Travellers’ Tales have ‘Burker’ stories, rooted in the murderous exploits of Burke and Hare who preyed on live human specimens as well as cadavers for supply to the Edinburgh anatomy school in the 1820s. The memory of Burke and Hare looms with menace in the collective Travellers’ memory and in the final piece in the book. ‘The Kenchins’ Ceilidh’ is a children’s re-enactment from this tradition. Stanley Robertson’s life is also revealed alongside the tales. From his work as a filleter in Aberdeen (a world explored in his memoir ‘Fish Hooses’) to becoming a well-known ballad singer and storyteller, these talents would take him to festivals throughout Europe, Britain and North America where they would lead to him being recognised as a teacher and cultural ambassador to the Travelling peoples of Scotland.

- Author:

- Marion Angus

- Publication Date:

- 1924

- Imprentit:

The Tinker’s Road

The black thorn’s maenin’,

“O rauch winds, let me be!

Atween ye a’

Ye’ve brak ma he’rt,

An’ syne I canna dee!”Weerin’ til a thread,

Smoored wi’ mosses reid,

The soople road wins ower the tap

An’ tak’s nor tent nor heed.Frae ‘The Tinker’s Road’