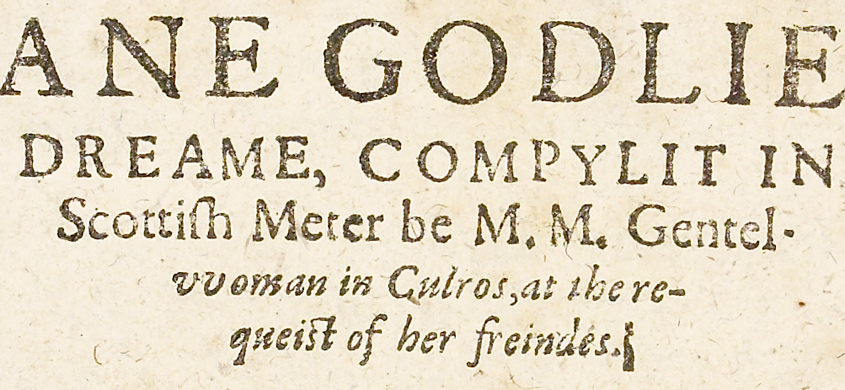

‘Ane Godlie Dreame, Compylit in Scottish Meter be M.M. Gentel-woman at Culross, as requestit of her friendes’ wis scrievit bi Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (ca1578-ca1640), an first imprentit in 1603 bi Robert Charteris in Edinbrugh.

Wi the inclusion o Melville’s ‘Ane godlie dreame’ in Germaine Greer’s ‘Kissing the rod: An anthology of 17th century women’s verse’ (1988), follaed by editor Catherine Kerrigan’s ‘An anthology of Scottish women poets’ (1991), the poetry o Elizabeth Melville haes become mair universally kent. Jamie Reid Baxter’s discovery in 2002 o previously unkent manuscripts scrievit in the haund o Elizabeth Melville, as set oot in his ‘Poems of Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross’ (2010) haes led tae a braider understaundin o Melville’s warld an verse.

Elizabeth Melville wis the first wumman in Scotland tae see her wark in prent. The popularity o the 1603 imprentin o ‘Ane godly dreame’ led tae it bein transcribit in English the follaein year, wi successive imprents makkin it a powerfu wark oot-throu the religious strauchles o the 17th century. Elizabeth Melville is myndit in the settin o a flagstane in her honour at Makars Coort in Edinbrugh, unhappit bi Germaine Greer in 2014. The Naitional Leebrar hauds copies o the 1603 Scots imprent an alsae a copy o the 1604 English translation, baith imprentit in Gothic copperplate, as weel as a 1694 English copy in staundart prent.

Lear mair aboot Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (ca 1578–ca 1640)

Elizabeth Melville follaed in the trend o scriptural verse as set oot in the ’Godly ballatis’, originally kent as ‘The Dundee psalms’ an attributit tae the Wedderburn brithers in 1567. She wis alsae in the ken o makar Alexander Montgomerie an religious poet Alexander Hume. It was throu a potent mixter o Calvinistic imagery wi weel-foondit traditions o Scots poetry that she ettled tae heeze up the Christian message o resurrection an salvation.

Foregane generations o Melville’s faimily wir insnorlt in the intrigues o the Reformation in Scotland. Her grandfaither wis executit fir takkin pairt in the Protestant cause in 1548, whiles faither Sir James Melville – kent fir scrievin memoirs wi regairds the relationship atween Scotland and France – served in baith the coort o Mary Queen o Scots then that o King James VI whiles uphaudin his Reformed faith. Elizabeth Melville wid hirsel become enshrined in Protestant folklore whan she wis said tae hae inspired an ootpoorin o the Haly Speerit at a seminal Covenanter’s Pentecost haudit at Kirk o Shotts in 1636.

‘Ane godlie dream’ begins wi the narrative vyce in the howes o contemplation ower the state o humanity an waesome fate o whit she descrives as ‘this fals(e) and iron age’. Fashed wi temptation she speirs o the Lord: ‘how lang the Sanctis shall be afflictit and how lang Subtill Satan rage?’ She pleads tae Lord Jesus tae ‘cam and saif thy awin Elect.’ Whiles in this heid-state she gangs tae rest whan an angel visits her dream. The divine vyce speirs anent her limits o forbeirance whaurby she replies she is ready tae tak flicht.

God taks her up in flicht, through mosses, clabbers, sheuchs, jags, watter an dreidfu dens; ower mountains, ugly braes o saund, across seas an great deserts. She feels dowie but he implores her tae gang on, ower brigs o trees that spang rivers lippin-fu wi devourin beasts. She dwynes again an langs tae sit or staund but the divine vyce tells her she maun thole an so she fins strynth aince mair.

She sees ‘the Castell glistering like gold and shyning silver bricht’, afore it ‘great pricks of iron’ that teir an rive at her feet as she rins ower them. Seein ‘the staitlie steps’ she breenges tawards thaim but does sae hastily withoot the command o God, whaurupon she is thrawn back doon afore he comforts her an tells her she maun luik ablow.

‘Whan this was done my heart did dance for joy’

I was sa near, I thocht my voyage endit:

I ran befoir, and socht not his convoy,

Nor speirit the way, because I thocht I kend it:

On staitlie steps maist stoutlie I ascendit,

Without his help I thocht to enter thair:

He followit fast and was richt sair offendit,

And haistilie did thraw mee down the stair.’

She glowers doon intae the pit tae see it brimmin wi fire an tortured souls, then asks God if this is ‘the Papists purging place.’ He tells her purgatory is an invention frae the brain o man then alludes tae fause kirk practices whaur redemption is exchynged fir peyment in gowd, whiles tellin her that ainly His bluid can save, leavin the ‘blyndit beists’ wi their ‘thochts all in vain.’ He tells her the pit is Hell an that she maun go through it but she thinks she hasn’ae the strynth. He assures her that His bluid wisn’ae shed in vain an that they shall nae bide lang in Hell.

They enter the pit, gangin ower burnin an tormentit souls, as ane raxes up an grips her an hauds her ‘heich above ane flaming fyre!’ She screichs fir the Lord wha taks haud o her again. She waukens frae the dream an recoonts its lesson, revisitin the perils o her flicht an seekin answers tae its quaistions:

‘The nearer heaven the harder the way.

The way to heaven, mon be throw Death and Hell’

Elizabeth Melville scrievit her poetry muckle in the Scots tradition, scrievin ‘Ane godlie dreame’ in ‘Ballat Royal’ metre as observit in King James VI’s ‘Ane Schort Treatise contening some Reulis and Cautelis tae be observit and eschewit in Scottis poesie’. ‘Ballat Royal’ wis a kenspeckle metrical form in earlier Scots, English an European poetry, whiles alliteration wis a raiglar featur in Early Scots poetry as exemplified in Sir Richard Holland’s ‘The Buke of the Howlat’.

In ‘Ane Schort Treatise’, which featurs as pairt o King James VI’s 1584 ‘Essays of a prentice in the divine art of poesie’, the poet King cooncels: ‘For any heich & grave subjectis, specially drawin out of learnit authoris, use this kynde of verse following, callit Ballat Royal.’ In the same imprent he scrieves ‘The CIIII Psalme, Translated out of Tremellius’ yaisin the same Ballat Royal metre as that yaised in Melville’s ‘Ane Godlie Dreame’ some 19 years eftir.

Jamie Reid Baxter’s ‘Poems of Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross’, alang wi its Eftirword leams faur greater licht on the life an times o Elizabeth Melville, whiles introducin hitherto undiscovert poems. It gies some context tae her wark in relation tae the contemporaneous verse o English poets Marlowe an Raleigh, as weel as the influence o Scots makar Montgomerie.

It gies furder insicht tae as tae hou Melville’s poetry wis thirled tae the religious an political intrigues o the time. Her poems constantly invoke Calvinistic themes o the Faw, Redemption an Grace, whiles the individual is seen tae be in direct communication wi the Haly Speerit, therby chimin wi the tenets o reformed faith. She defied Royal authority bi scrievin potentially treasonous poems in support o religiopolitical prisoners.

The flagstane in Makars Coort in Edinbrugh, unhappit bi Germaine Greer in the 2014 ceremony tae commemorate Elizabeth Melville, is inscribit wi lines frae ‘Ane godlie dreame.’

‘Though Tyrants threat, though Lyons rage and rore

Defy them all, and feare not to win out’.

‘Ane Godlie Dreame, Compylit in Scottish Meter be M.M. Gentel-woman at Culross, as requestit of her friendes’ was written by Elizabeth Melville, Lady of Culross (ca1578-ca1640), and first published in 1603 by Robert Charteris in Edinburgh.

With the inclusion of Melville’s ‘Ane Godlie Dreame’ in Germaine Greer’s ‘Kissing the Rod: An Anthology of 17th Century Women’s Verse’ (1988), followed by editor Catherine Kerrigan’s ‘An Anthology of Scottish Women Poets’ (1991), the poetry of Elizabeth Melville has become more universally known. Jamie Reid Baxter’s discovery in 2002 of previously unknown manuscripts written in the hand of Elizabeth Melville, as set out in his ‘Poems of Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross’ (2010) has led to a wider understanding of Melville’s world an poetry.

Elizabeth Melville was the first woman in Scotland to have her work published. The popularity of the 1603 publication of ‘Ane Godly Dreame’ led to it being transcribed in English the following year, with successive publications making it a powerful work throughout the religious conflicts of the 17th century. Elizabeth Melville was commemorated in the setting of a flagstone in her honour at Makars Court in Edinburgh, unveiled by Germaine Greer in 2014. The National Library holds copies of the 1603 Scots publication and 1604 English translation, both printed in Gothic copperplate, as well as a 1694 English copy in standard print.

Learn more about Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (ca 1578–ca 1640)

Elizabeth Melville followed in the trend of scriptural verse as set out in the ’Godly ballatis’, originally known as ‘The Dundee psalms’ an attributed to the Wedderburn brothers in 1567. She was also known to Scottish court poet Alexander Montgomerie an religious poet Alexander Hume. It was through a potent mixture of Calvinistic imagery with well-founded traditions of Scots poetry that she resolved to promulgate the Christian message of resurrection and salvation.

Former generations of Melville’s family were involved in the intrigues of the Reformation in Scotland. Her grandfather was executed for taking part in the Protestant cause in 1548, while father Sir James Melville – known for writing memoirs with regards the relationship between Scotland and France – served in both the court of Mary Queen of Scots then that of King James VI while upholding his reformed faith. Elizabeth Melville would herself become enshrined in Protestant folklore when she was said to have inspired an outpouring of the Holy Spirit at a seminal Covenanter’s Pentecost held at Kirk o Shotts in 1636.

‘Ane godlie dream’ begins with the narrative voice in the depths of contemplation over the state of humanity and the sorrowful fate of what she describes as ‘this fals(e) and iron age’. Troubled with temptation she asks of the Lord: ‘how lang the Sanctis shall be afflictit and how lang Subtill Satan rage?’ She pleads to Lord Jesus to ‘cam and saif thy awin Elect.’ While in this state of mind she goes to retire when an angel visits her dream. The divine voice asks about her limits of endurance whereby she replies she is ready to take flight.

God takes her up in flight, through mosses, mires, ditches, thorns, water and dreadful dens; over mountains, ugly hills of sand, across seas and great deserts. She feels fatigued but he implores her to go on, over bridges of trees that span rivers filled with devouring beasts. She becomes exhausted again and longs to sit or stand but the divine voice tells her she must endure and so she finds strength once more.

She sees ‘the Castell glistering like gold and shyning silver bricht’, before it ‘great pricks of iron’ that tear and rent at her feet as she runs over them. Seeing ‘the staitlie steps’ she rushes towards them but does so hastily without the command of God, whereupon she is thrown back down before he comforts her and tells her she must look below.

‘Whan this was done my heart did dance for joy’

I was sa near, I thocht my voyage endit:

I ran befoir, and socht not his convoy,

Nor speirit the way, because I thocht I kend it:

On staitlie steps maist stoutlie I ascendit,

Without his help I thocht to enter thair:

He followit fast and was richt sair offendit,

And haistilie did thraw mee down the stair.’

She stares down into the pit to see it brimming with fire and tortured souls, then asks God if this is ‘the Papists purging place.’ He tells her purgatory is an invention from the brain of man then alludes to false church practices where redemption is exchanged for payment in gold, while telling her that only His blood can save, leaving the ‘blyndit beists’ with their ‘thochts all in vain.’ He tells her the pit is Hell and that she must go through it but she thinks she doesn’t have the strength. He assures her that His blood was not shed in vain and that they shall not remain long in Hell.

They enter the pit, going over burning and tormented souls, as one reaches up and grips her to hold her ‘heich above ane flaming fyre!’ She screeches for the Lord who takes hold of her again. She wakens from the dream and recounts its lesson, revisiting the perils of her flight an seeking answers to its questions:

‘The nearer heaven the harder the way.

The way to heaven, mon be throw Death and Hell’

Elizabeth Melville wrote her poetry very much in the Scots tradition, writing ‘Ane Godlie Dreame’ in ‘Ballat Royal’ metre as observed in King James VI’s ‘Ane Schort Treatise contening some Reulis and Cautelis tae be observit and eschewit in Scottis poesie’. ‘Ballat Royal’ was a familiar metrical form in earlier Scots, English an European poetry, while alliteration was a regular feature in Early Scots poetry as exemplified in Sir Richard Holland’s ‘The Buke of the Howlat’.

In ‘Ane Schort Treatise’, which features as part of King James VI’s 1584 ‘Essays of a prentice in the divine art of poesie’, the poet King counsels: ‘For any heich & grave subjectis, specially drawin out of learnit authoris, use this kynde of verse following, callit Ballat Royal.’ In the same publication he writes ‘The CIIII Psalme, Translated out of Tremellius’ using the same Ballat Royal metre as that used in Melville’s ‘Ane godlie dreame’ some nineteen years after.

Jamie Reid Baxter’s ‘Poems of Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross’, along with its Afterword shines far greater light on the life and times of Elizabeth Melville, while introducing hitherto undiscovered poems. It gives some context to her work in relation to the contemporaneous verse of English poets Marlowe and Raleigh, as well as the influence of Scots makar Montgomerie.

It gives further insight too as to how Melville’s poetry was tied to the religious and political intrigues of the time. Her poems constantly invoke Calvinistic themes of the Fall, Redemption and Grace, while the individual is seen to be in direct communication with the Holy Spirit, consistent with the tenets of reformed faith. She defied Royal authority by writing potentially treasonous poems in support of religiopolitical prisoners.

The flagstone in Makars Coort in Edinburgh, unveiled by Germaine Greer in the 2014 ceremony to commemorate Elizabeth Melville, is inscribed with lines from ‘Ane godlie dreame.’

‘Though Tyrants threat, though Lyons rage and rore

Defy them all, and feare not to win out’.

- Author:

- Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross

- Publication Date:

- 1603

- Imprentit:

Edinburgh

Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross

‘With siches and sobs as I did so lament,

Into my dreame I thocht thair did appear

Ane sicht maist sweit, quhilk maid me well content:

Ane Angell bricht with visage schyning cleir,

With luifing luiks and with ane smyling cheir

He askit me, quhy art thou thus sa sad?

Quhy grones thou so? Quhat dois thou dwyining heir

With cairfull cryes in this thy bailfull bed?Frae ‘Ane Godlie Dreame’