Gavin Douglas’ Eneados, the first full owersettin o ony major classical work intae an Anglic leid, is yin o the keystanes o Scots literatur. Completit in 1513 an widely creditit wi gien the name ‘Scots’ tae the language, the Eneados is still a treisur-trove tae scholars an a delite tae readers.

The cultural significaunce o Douglas’ owersettin o the Aeneid raxes faur ayont the language o its scrievin. Recognised bi sic illuminars as Ezra Pound an C.S. Lewis as yin o the muckle moniments o western literatur, the Eneados remeens peerless in the smeddum o its poetry an the pure pouer o its storytellin mair than five hunner years efter its composition.

Lear mair aboot Eneados bi Gavin Douglas

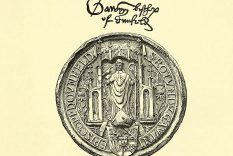

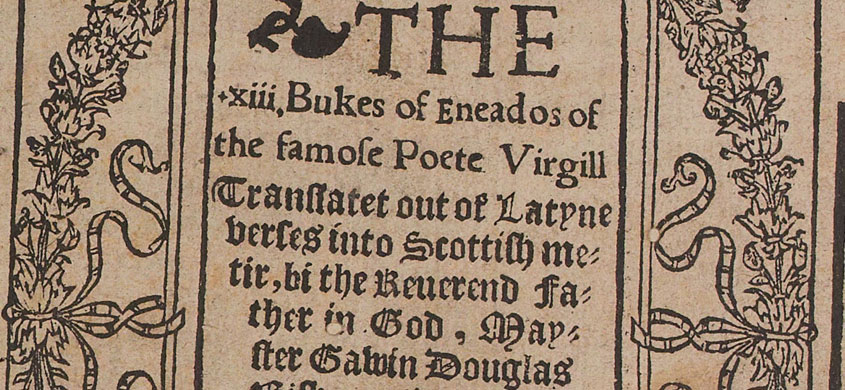

It is maistly thanks tae his political an ecclesiastical career that we ken sae muckle, at sic great remuive, aboot the life o Gavin Douglas. Born at Tantallon Castle in East Lothian in 1474, an son tae the 5th Earl o Angus, Douglas an his faimily played a pivotal role in the shapin an reshapin o Scotland efter the deith o James IV at the Battle o Flodden. Provost o St Giles in Embra an – efter nae sma portion o political joukerie – Bishop o Dunkeld, Douglas’s copious correspondence wi the high heid yins o Scotland an England mak him yin o the better-documentit figurs o his time. Houaniver, if it is thanks tae Douglas’s public life that we micht ken him still, it is due purely tae his literary career that we remember him. Finisht in 1513, his final scrievit wirk afore Flodden an its eftercast flung him halely intae affairs o state, Douglas’ Eneados is in mony weys less an owersettin than an Aeneid o Scotland’s ain, a national epic frae which an entire national literatur erupts, an tae which an entire national literatur can trace its soorce.

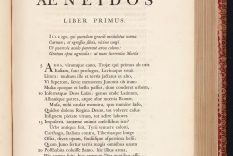

Tho Virgil’s Aeneid had been partially owerset intae mony ither leids, an fully (but, tae Douglas’ view, unsatisfactorilie) owerset intae French, Douglas’ Eneados marked the first full owersettin o ony wirk o classical antiquity intae ony vernacular language. That the language in quaisten happened tae be Scots – Douglas gans oot his wey in the prologue tae explicitly distinguish his native leid fae ‘sudroun’ English, gien a name tae the Scottish tongue for whit micht be the first recordit time – has by nae means keepit his wirk fae raxin readers aw aroond the warld.

The story o the Aeneid requires little further gloss. The antrin adventurs that interspace the traivels o its hero, Aeneas, frae Troy tae Italy, hiv lang syne entered in tae oor skared vocable o idioms an images – the Trojan Horse, the descent intae the Unnerwarld, the tragedy o Queen Dido. But gin the stories are familiar tae us, it is like as no thanks tae Douglas’ owersettin, which remeens the gowd staundart for versions o Virgil, an tae this verra day the medium throu which mony hae experienced yin o the great wirks o classical literatur. Douglas’ insertion intae the text o his ain original prologues tae each o the poem’s twal buiks, as weel as his idiosyncratic inclusion o the poem’s ‘thirteenth’ buik – scrievit no by Virgil, but by 15th century Italian poet Maffeo Vegio – hae makkit shuir that, for five hunner years an mair, readers o the Aeneid hae deeked throu Douglas’ goamin een, raither than jist their ain.

Forby the worthiness o Douglas’ wirk in its ain richt, the importance o the Eneados as a formative maument for baith the leid an the literatur o Scotland can haurdly be owerstatit. In his Prologue tae Buik I, Douglas sets oot a kind o manifesto for the Scots leid, an maks heidy defence o its fitness tae tell the story o Aeneas.

Na ʒit so clene, all sudroun I refuse

Bot sum worde I pronuce, as nychboure dois

Like as in latine bene, grewe termes sum

So me behuffit quhilum or be dum

Sum bastard latyne, Frensche or ynglis ois

Quhare scant wes scottis, I had nane vthir chois.

(Prologue tae Buik I, lines 113-118)

In this wey merkin oot his text as Scots wi English borrowins, raither than English padded oot wi Scots, Douglas micht weel hae makkit the first kenmerk on the map tae modren Scots. Lend-wirds fae ither tongues acceleratit the divergence o Scots fae its sib-leid English, an Douglas’ sel-admittit reivins o the dictionars o ither leids were tae hae a profoond effect on the weygate o the Scots vocable. Consider Douglas’s borrowins fae the languages o the Flemish, wha had cam tae Scotland in their draves efter their expulsion fae England in 1154, an formed a muckle community near Douglas’ provostship at St Giles. In order tae fully rander the vaiges o his Aeneas, Douglas cast his net an borrowed widely fae the nautical vocable o his sea-farin neebours, the mercantile Flemish, thereby introducin tae the Scots leid sic wirds as ‘bel’ (bubble), ‘helmstok’ (tiller) an – nae owersettin needit, shuirly – ‘scone’. It’s wirth notin forby that gin scone seems like an anachronism here, mynd as weel that it’s also tae the Eneados that we awe the first recordit appearance o the wird ‘wow’.

The five centuries that separate us fae the scrievin o Douglas’ final line hae witnessed some gey roch haunlin o his wirk. Ettlins at new-fanglin his poetry – chyngin its meters, correctin its owersettins, daein awa wi its Scots – hae been ceaseless. Yet it’s the attempts at modrenisation that hae driftit intae the past, the skaikins ower o his canvasses that hae cracked an peeled awa. Ower the lifetimes o kintraes an the dingin doun o castles, the poetry o Gavin Douglas still soonds tae us, lood an clear, a brig athort time, while the vyces that meant tae droon his oot hae dwyned awa tae echo.

Gavin Douglas’ Eneados, the first full translation of any major classical work into an Anglic tongue, is one o the keystones of Scots literature. Completed in 1513 and widely credited with giving the name ‘Scots’ to the language, the Eneados is still a treasure-trove to scholars and a delight to readers.

The cultural significance of Douglas’ translation of the Aeneid reaches far beyond the language of its composition. Recognised by such luminaries as Ezra Pound and C.S. Lewis as one of the great monuments of western literature, the Eneados remains matchless in the vigour of its poetry and the raw power of its storytelling more than five hundred years after it was written.

Learn more about Eneados bi Gavin Douglas

It is mostly due to his political and ecclesiastical career that we know so much, at such great remove, about the life of Gavin Douglas. Born at Tantallon Castle in East Lothian in 1474, and son to the 5th Earl of Angus, Douglas and his family played a pivotal role in the shaping and reshaping of Scotland following the death of James IV at the Battle of Flodden. Provost of St Giles in Edinburgh and – after no small amount of political manoeuvring – Bishop of Dunkeld, Douglas’ copious correspondence with the nobility of Scotland and England make him one of the better-documented figures of his time. However, if it is thanks to Douglas’ public life that we might know him yet, it is due purely to his literary career that we remember him. Completed in 1513, his final written work before Flodden and its aftermath cast him wholly into affairs of state, Douglas’ Eneados is in many ways less a translation than an Aeneid of Scotland’s own, a national epic from which an entire national literature erupts, and to which an entire national literature can trace its source.

Though Virgil’s Aeneid had been partially translated into several other languages, and fully (but, to Douglas’ view, unsatisfactorily) translated into French, Douglas’ Eneados marked the first full translation of any work of classical antiquity into any vernacular language. That the language in question happened to be Scots – Douglas goes out of his way in the prologue to explicitly distinguish his native language from ‘sudroun’ English, giving a name to the Scottish tongue for what may well be the first recorded time – has by no means prevented his work from reaching readers all around the world.

The story of the Aeneid requires little further gloss. The strange adventures which populate the travels of its hero, Aeneas, from Troy to Italy, have long since entered into our collective vocabulary of idioms and images – the Trojan Horse, the descent into the Underworld, the tragedy of Queen Dido. But if the stories are familiar to us, it is likely as not thanks tae Douglas’ translation, which remains the gold standard for versions of Virgil, and to this very day the medium through which many have experienced one of the great works of classical literature. Douglas’s insertion into the text of his own original prologues to each of the poem’s twelve books, as well as his idiosyncratic inclusion of the poem’s ‘thirteenth’ book – written not by Virgil, but by 15th century Italian poet Maffeo Vegio – have made sure that, for five hundred years and more, readers of the Aeneid have viewed it through Douglas’ ever-observant eyes, rather than just their own.

Besides the worthiness of Douglas’ work in its own right, the importance of the Eneados as a formative moment for both the language and the literature of Scotland can hardly be overstated. In his Prologue to Book I, Douglas sets out a kind of manifesto for the Scots language, and makes passionate defence of its fitness to tell the story of Aeneas.

Na ʒit so clene, all sudroun I refuse

Bot sum worde I pronuce, as nychboure dois

Like as in latine bene, grewe termes sum

So me behuffit quhilum or be dum

Sum bastard latyne, Frensche or ynglis ois

Quhare scant wes scottis, I had nane vthir chois.

(Prologue to Book I, lines 113-118)

In this way identifying his text as Scots with English borrowings, rather than English bolstered by Scots, Douglas might well have drawn the first stroke on the map to modern Scots. Loan-words from other tongues accelerated the divergence of Scots from its sibling-language English, and Douglas’ self-admitted plunderings from the dictionaries of other languages were to have a profound effect on the expansion of the Scots vocabulary. Consider Douglas’ borrowings from the languages of the Flemish, who had arrived in Scotland in their droves after their expulsion from England in 1154, and formed a sizable community near Douglas’s provostship at St Giles. In order to fully render the voyages of his Aeneas, Douglas cast his net and borrowed widely from the nautical vocabulary of his sea-faring neighbours, the mercantile Flemish, thereby introducing to the Scots language such words as ‘bel’ (bubble), ‘helmstok’ (tiller) an – no translation necessary, surely – ‘scone’. It’s worth noting at this point that if scone seems like something of an anachronism, bear in mind that it’s also to the Eneados that we owe the first recorded appearance o the word ‘wow’.

The five centuries which separate us from the penning of Douglas’ final line have witnessed some rather rough handling of his work. Attempts at bringing his poetry up-to-date – changing its meters, correcting its translations, toning down its Scots – have been ceaseless. Yet it’s these strivings towards modernisation that have inevitably drifted into the past, the daubing-over of his canvasses that have cracked and peeled away. Over the lifetimes of countries and the falling-downs of castles, the poetry of Gavin Douglas still sounds to us, loud and clear, a bridge across time, while the voices that meant to drown his out have faded away to echo.

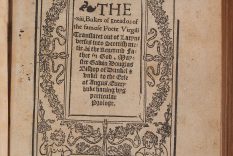

- Author:

- Gavin Douglas

- Publication Date:

- 1553

- Imprentit:

Edinburgh

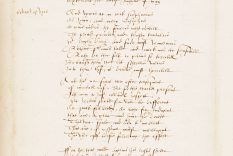

Prologue to the Buke I

Na ʒit so clene, all sudroun I refuse

Bot sum worde I pronuce, as nychboure dois

Like as in latine bene, grewe termes sum

So me behuffit quhilum or be dum

Sum bastard latyne, Frensche or ynglis ois

Quhare scant wes scottis, I had nane vthir chois.Prologue to Buke I, lines 113-118