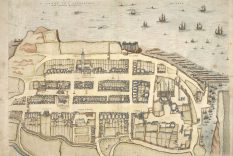

The ancient university toon o St Andraes aiblins isnae thocht o as a centre o Scots language the day. Durin the reign o King James VI an I, hooiver, Scots was the language o government an law, literature an officialdom, forby the iverday leid o kings an scholars, courtiers an commoners alike – includin in St Andraes.

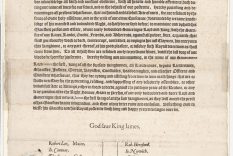

This is weel illustratit in a letter – datin fae 1611 – fae the high-heid yins at the University o St Andraes tae King James, fur tae thank him fur his let-on intention tae provide siller fur the biggin o a new library. The letter exemplifies a wheen o kenspeckle Middle Scots merkers, sic as ‘quh’ (equivalent tae modren ‘wh’) in wirds sic as ‘quhairby’, ‘fumquhat’ an ‘quho’; the past tense inflection ‘-it’, as in ‘informit’; plurals in ‘-is’ sic as in ‘buikis’; the spellin convention ‘thair’, as in, fur example, ‘thairof’ an ‘thairto’; an the voiceless velar fricative as in ‘nocht’, ‘throche’ an ‘Almichtie’. Forby we see a hantle o Scots wirds that are aye kenable in modren Scots the day, fur example, ‘kirk’, ‘commoune-veil’ an the wird ‘ane’, which aye functions as the numeral 1 as weel as the indefinite airticle.

Hae a wee look at this bittie fae the stert o the letter, fur exemple, which sets the scene by referrin tae the:

‘Archbifhop of Sanctandroufs, our werie prudent chanceller, hauing informit vs, the Rector, Deanes of Faculties, and remanent Maifteris of your majefties Vniuerfitie of Sanctandrous, hou cairful your majestie is of the florishing estait thairof, particularlie of the dedicatioune of ane commoune Bibliotheque thairto, quhairby learning (throche bypaft penurie of buikis fumquhat decaying) may be, to the benefit of the kirk and commoune-veil, refufcitat…” [p. 200 Letters and State Papers]

Lear mair aboot The King James Library, St Andraes

The mither o James, Mary Queen o Scots, had scrievit a will bequeathin her Greek an Latin buiks tae the university fur the foondin o a library. This is likely tae hae been ahint King James’s decision tae fund the biggin o sic in St Andraes.

Though the letter referrin tae the library dates fae 1611, financial trauchles meant that it wisnae completit afore 1643. Biggit on the site o the earlier medieval College o St John (whaur teachin had begun at the university in the 1400s), the biggin visible the day dates fae the 1600s, though pairts o the earlier biggin were incorporatit intae the new structure. The King James Library the day is a dedicatit Divinity library an aye a braw place o study in the university toon.

Lear mair aboot King James VI an I

James VI o Scotland (1567-1625) an I o England (1603-1625) was the lest Scots-speikin an scrievin monarch o Scotland. It’s weel-kent that the Reformation, in particular the dominance o English leid bibles, sparkit the douncome o Scots as a prestige an institutional leid. The flittin o king and court tae Lunnon in the Union o the Croons in 1603, whan James VI o Scotland becam James I o England forby, was anely tae exacerbate thon further.

Afore then, hooiver, as King James VI o Scotland (36 o the 58 year o his reign), James ruled ower a kintra whaur Scots was the language o government an law, literature an officialdom, as weel as the iverday leid o kings an scholars, courtiers an commoners alike.

Forby, James was a prolific scriever, owersetter an intellectual. A self-styled ‘philosopher-king’, he is soondly threapit as ane o the maist scholarly monarchs in history an siccarly the maist furthset British ruler. Throughoot his life, James scrievit a muckle range an volume o wark, includin in Scots, fae political an religious scrievins, tae poetry an owersettins, an treatises on themes as sindry as tobacco an witchcraft. He wis forby the patron o monie mensefu scrievers, includin Shakespeare, an is, o coorse, aiblins best-kent as the patron o the noo warld famous ‘Authorised’ or King James Bible.

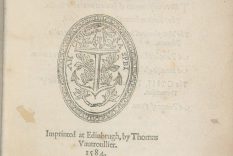

Ane o his earliest warks was a treatise on poetry entitlet ‘Ane Schort Treatise, Conteining Some Reulis and Cautelis to be Observit and Eschewit in Scottis Poesie’, scrievit by James whan he was 17 an setten furth in 1584. A guide tae the scrievin o poetry in Scots, appropriately, it is scrievit in braid Middle Scots, an replete wi merkers sic as ‘quh-‘, the ‘-it’ past tense inflexion an ‘-is’ plural forms forms, forby monie Scots lexical items. Tae quote fae the beginnin o the wark, fur exemple: ‘Bot as to this work, quhilk is intitulit, The Reulis and cautelis to be observit & eschewit in Scottis Poesie, ze may marvell paraventure, quhairfore I should have…’

Forby his clear command an yaise o Scots, it would appear that James was in nae doot that Scots was a sindry leid tae English, aabeit that the twa were closely relatit. In the preface tae the wark, James scrievit:

‘The uther cause [o scrievin this treatise] is that for thame that hes writtin in it [i.e. anent poesie] of late, there hes never ane of thame writtin in our language. For albeit sindrie hes written of it in English, quhilk is lykest to our language, yit we differ from thame in sindrie reulis of poesie, as ye will find be experience.’

Lowp forrit tae 1603, hooiver – whan James had inheritit the croon o England follaen the death o Queen Elizabeth wioot an heir – an he nou seems blythe tae pley doon onie differences atween Scots an English fur tae further his political aspirations o unitin the twa kingdoms that he heidit (indeed, James was the first monarch tae style hisel as King o Great Britain, although he ne’er did succeed in his aim o fou political union). In a speech tae the Pairlament in Lunnon in May 1603, James threapit fur union in the follaen terms:

‘But what should we sticke upon any naturall appearance, when it is manifest that God by his Almightie providence hath preordained it so to be? Hath not God first united these two Kingdomes both in Language, Religion and similitude of manners?’

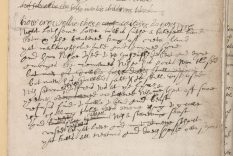

We ken, forby, that late Middle Scots manuscripts scrievit in James’s haun were syne anglicised by his printers afore furthsettin. Though it’s unsiccar tae whit extent the king wis involvit in this process o anglicisation, Rhodes, Richards an Marshall mak the pynt in their ‘King James VI and I: Selected Writings’ that ‘…Dæmonologie (1597) and Basilicon Doron (1599, 1603), which both exist in manuscripts written in late Middle Scots in James’s own hand, were anglicised by his printer, Robert Waldegrave, prior to publication. Since both texts were published in this form in Edinburgh before Elizabeth’s death, it seems clear that James was already using the press to advertise himself to his future subjects in a language that would make him seem less alien.’ (p.2)

The same authors conclude that ‘James’s transition from a writer committed to promoting a distinctively Scottish literature to one speaking the language of the future British state might be described as the first act of union.’ (p.2)

A hale buik or PhD could nae doot be scrievit anent King James VI an I an his shiftin yaise o Scots an English, but it’s clear fae the abuin that complex political an personal factors were at pley in the linguistic choices o the lest Scots-speikin an scrievin monarch o Scotland.

Noo that we’ve had a closer look at King James VI an I, let’s hae a look at the letter fae the University o St Andraes in a wee bittie mair detail. As seen abuin, the letter, which dates fae 4 May, 1611, sets the scene by referrin tae the ‘Archbifhop of Sanctandroufs, our werie prudent chanceller, hauing informit vs, the Rector, Deanes of Faculties, and remanent Maifteris of your majefties Vniuerfitie of Sanctandrous, hou cairful your majestie is of the florishing estait thairof, particularlie of the dedicatioune of ane commoune Bibliotheque thairto, quhairby learning (throche bypaft penurie of buikis fumquhat decaying) may be, to the benefit of the kirk and commoune-veil, refufcitat…’

The high-heid yins o the university gang on tae thank the King in terms sae unreservit that they appear a wee bitte obsequious tae modren een, an tae urge him tae mak guid on his promise:

‘ve ca nocht vithout the blot of deteftable ingratitude and excuifable vndeutifulnes to your majeftie as our moft gratious and beneficent prince, bot vithe all humilitie of mynd and bodie, moft hartlie thanke your majeftie thairfoir…and, vith the lyk humilitie in houp to be hard, moft earniftlie intreat your majestie to perfytly profecute that particulare purpoife of liberalitie touardis vs.’

Syne, concludin, they state that:

‘…vee, frome the bottome of our hartis, vniformlie recommend your majefties royal perfoune and eftait to the Almichtie God, quho may blefs your majeftie in this lyf vith a long and profperous raigne; and with ane eternal and glorious in the lyf to cum. Your Majefties moft humble and obedient feruitoris and fubjectis…’

Throughoot the letter, we see monie exemples o the kenspeckle Middle Scots merkers referred tae abuin, fae the ‘quh’ in wirds sic as ‘quhairby’ tae the ‘-is’ plural.

The ancient university town of St Andrews perhaps isn’t thought of as a centre of Scots language today. During the reign of King James VI and I, however, Scots was the language of government and law, literature and officialdom, as well as the everyday language of kings and scholars, courtiers and commoners alike – including in St Andrews.

This is well-illustrated in a letter – dating from 1611 – from the university authorities to King James to thank him for his indicated intention to provide money for the building of a new library. The letter exemplifies a whole host of definitive Middle Scots markers, such as ‘quh’ (equivalent to modern ‘wh’) in words such as ‘quhairby’, ‘fumquhat’ and ‘quho’; the past tense inflection ‘-it’, as in ‘informit’; plurals in ‘-is’ such as in ‘buikis’; the spelling convention ‘thair’, as in, for example, ‘thairof’ and ‘thairto’; and the voiceless velar fricative as in ‘nocht’, ‘throche’ and ‘Almichtie’. In addition, we see a range of Scots words that are still recognisable in modern Scots today, for example, ‘kirk’, ‘commoune-veil’ and the word ‘ane’, which still functions as the numeral 1 as well as the indefinite article.

Have a wee look at this excerpt from the start of the letter, for example, which sets the scene by referring to the:

‘Archbifhop of Sanctandroufs, our werie prudent chanceller, hauing informit vs, the Rector, Deanes of Faculties, and remanent Maifteris of your majefties Vniuerfitie of Sanctandrous, hou cairful your majestie is of the florishing estait thairof, particularlie of the dedicatioune of ane commoune Bibliotheque thairto, quhairby learning (throche bypaft penurie of buikis fumquhat decaying) may be, to the benefit of the kirk and commoune-veil, refufcitat…” [p. 200 Letters and State Papers]

Learn more about The King James Library, St Andraes

The mother of James, Mary Queen of Scots, had written a will bequeathing her Greek and Latin books to the university for the foundation of a library. It is likely that this lay behind King James’s decision to fund the building of such in St Andrews.

Although the letter referring to the library dates from 1611, financial difficulties meant that it was not completed before 1643. Built on the site of the earlier medieval College of St John (where teaching had begun at the university in the 1400s), the building visible today dates from the 1600s, though parts of the earlier building were incorporated into the new structure. Today, the King James Library is a dedicated Divinity library and remains a cherished place of study in the university town.

Learn more about King James VI and I

James VI of Scotland (1567-1625) and I of England (1603-1625) was the last monarch of Scotland who spoke and wrote in Scots. It is widely acknowledged that the Reformation, in particular the dominance of English language bibles, sparked the demise of Scots as a prestige and institutional language. The removal of king and court to London following the Union of Crowns in 1603, when James became king of England as well as of Scotland, was only to exacerbate the situation further.

Before then, however, as King James VI of Scotland (36 of the 58 years of his reign), James ruled over a country where Scots was the language of government and law, literature and officialdom as well as the everyday language of kings and scholars, courtiers and commoners alike.

Significantly, James was himself a prolific writer, translator and intellectual. A self-styled ‘philosopher king’, he is justifiably claimed as one of the most scholarly monarchs in history and was certainly the most-published British ruler. Throughout his life, James produced a wide range and high volume of work, including in Scots, from political and religious writings, poetry and translations, to treatises on themes as diverse as tobacco and witchcraft. In addition, he was the patron of many significant writers, including Shakespeare, and he is, of course, perhaps best known for his patronage of the now world famous ‘Authorised’ or King James Bible.

One of his earliest works was a treatise on poetry entitled ‘Ane Schort Treatise, Conteining Some Reulis [Rules] and Cautelis [Cautions] to be Observit and Eschewit in Scottis Poesie’, written by James when he was 17 and published in 1584. A guide to the writing of poetry in Scots, appropriately, it is written in broad Middle Scots, and replete with markers such as ‘quh-’, the ‘-it’ past tense inflexion and ‘-is’ plural forms forms, in addition to many Scots lexical items. To quote from the beginning of the work, for example: ‘Bot as to this work, quhilk is intitulit, The Reulis and cautelis to be observit & eschewit in Scottis Poesie, ze may marvell paraventure, quhairfore I should have…’

In addition to his clear command and usage of Scots, it would appear that James was in no doubt that Scots was a different language to English, albeit that the two were closely related. In the preface to the work, James wrote:

‘The uther cause [of writing this treatise] is that for thame that hes writtin in it [i.e. about poetry] of late, there hes never ane of thame writtin in our language. For albeit sindrie hes written of it in English, quhilk is lykest to our language, yit we differ from thame in sindrie reulis of poesie, as ye will find be experience.’

Fast forward to 1603, however – when James had inherited the crown of England following the death of Queen Elizabeth without an heir – and he now appears content to play down any differences between Scots and English in order to further his political aspirations of uniting the two kingdoms that he headed (indeed, James was the first monarch to style himself as King of Great Britain, although he never succeeded in his aim of full political union).

In a speech to the Parliament in London in 1603, James argued for union in the following terms: ‘But what should we sticke upon any naturall appearance, when it is manifest that God by his Almightie providence hath preordained it so to be? Hath not God first united these two Kingdomes both in Language, Religion and similitude of manners?’

We also know that Middle Scots manuscripts written in James’s hand were subsequently anglicised by his printers before publication. Although it’s uncertain to what extent the king was involved in this process of anglicisation, Rhodes, Richards and Marshall make the point in their ‘King James VI and I: Selected Writings’ that ‘…Dæmonologie (1597) and Basilicon Doron (1599, 1603), which both exist in manuscripts written in late Middle Scots in James’s own hand, were anglicised by his printer, Robert Waldegrave, prior to publication. Since both texts were published in this form in Edinburgh before Elizabeth’s death, it seems clear that James was already using the press to advertise himself to his future subjects in a language that would make him seem less alien.’ (p.2)

The same authors conclude that ‘James’s transition from a writer committed to promoting a distinctively Scottish literature to one speaking the language of the future British state might be described as the first act of union.’ (p.2)

A whole book or PhD could doubtless be written about King James VI and I and his shifting usage of Scots and English. However, it is clear from the above that complex political and personal factors were at play in the linguistic choices of the last Scots-speaking and writing monarch of Scotland.

Now that we’ve had a closer look at King James VI and I, let’s have a look at the letter from the University of St Andrews in a bit more detail. As seen above, the letter, which dates from 4 May 1611, sets the scene by referring to the ‘Archbifhop of Sanctandroufs, our werie prudent chanceller, hauing informit vs, the Rector, Deanes of Faculties, and remanent Maifteris of your majefties Vniuerfitie of Sanctandrous, hou cairful your majestie is of the florishing estait thairof, particularlie of the dedicatioune of ane commoune Bibliotheque thairto, quhairby learning (throche bypaft penurie of buikis fumquhat decaying) may be, to the benefit of the kirk and commoune-veil, refufcitat…’

The university authorities go on to thank the king in terms so unreserved that they appear a wee bit obsequious to modern eyes, and to urge him to make good on his promise:

‘ve ca nocht vithout the blot of deteftable ingratitude and excuifable vndeutifulnes to your majeftie as our moft gratious and beneficent prince, bot vithe all humilitie of mynd and bodie, moft hartlie thanke your majeftie thairfoir…and, vith the lyk humilitie in houp to be hard, moft earniftlie intreat your majestie to perfytly profecute that particulare purpoife of liberalitie touardis vs.’

Then, concluding, they state that:

‘…vee, frome the bottome of our hartis, vniformlie recommend your majefties royal perfoune and eftait to the Almichtie God, quho may blefs your majeftie in this lyf vith a long and profperous raigne; and with ane eternal and glorious in the lyf to cum. Your Majefties moft humble and obedient feruitoris and fubjectis…’

Throughout the letter, we see many examples of the definitive Middle Scots markers referred to above, from the ‘quh’ in words such as ‘quhairby’ to the ‘-is’ plural.

- Author:

- University of St Andrews

- Publication Date:

- 1611

- Imprentit:

St Andrews

Letter from the University of St Andrews to James VI

…’Hou cairful your maiestie is of the florishing estait thairof, particularlie of the dedicatioune of ane commoune Bibliotheque thairto, quhairby learning (throche bypast penurie of buikis somquhat decaying) may be, to the benefit of the kirk and commoune-veil, resuscitat…’