‘Martha Spreull, Being Chapters in the Life of a Single Wumman’, imprentit in 1887 is a licht-hertit an joco novella set in Glesga an scrievit in braid Scots. It wis scrievit bi Henry Johnston unner the pseudonym Zachary Fleming. Johnston’s collectit sketches o Martha Spreull wir originally serialised in an imprent cried ‘Quiz.’

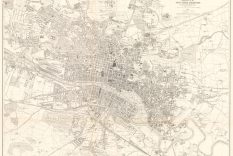

Johnston wis born in Northren Ireland bit his faimily wid flit tae Glesga when he wis three year auld. He wid spend the lave o his days there an become a kenspeckle figure in public life, bein ane o the original members o the Glasgow Ballad Club an servin as its President. He became kent as author o a wheen o novels in the kailyaird tradition an wis comparit wi the likes o George MacDonald an JM Barrie. His novels includit ‘The Chronicles of Glenbuckie’. Like the earlier novels o Galt an Scott these wid yaise English narrative wi chairacter vyces in Scots. ‘Martha Spreull’, forby an introduction an closing note bi the editor, is scrievit entirely in Scots an gies a kythin tae Glesga speech frae taewards the end o the 19th century.

Contrair tae the couthy tones o Martha Spreull, the Glesga novel o the follaein modren period, bi scrievers sic as Patrick MacGill, John McNeillie an George Blake, as weel as plays sic as Ena Lamont Stewart’s ‘Men Should Weep’ – wi themes o violence, exploitation an poverty – wid kythe the daurker aspecks o Glesga life. Throu the vyces o ther chairacters, these literary an dramatic warks, amang a gey wheen ithers, gie a kythin tae linguistic shifts in the Scots tung ower a period o time.

Lear mair aboot Martha Spreull an Glesga Scots

‘I am real muckle fashed wi’ my head, especially when I get a waff o’ cauld; and since I wrote last I have had a wonnerfu’ sair brash, which accounts, in pairt, for my backwardness in beginning this chapter. I have already tell’d ye hoo my interest in the higher forms o edication began by the opening o my flett o rooms, efter the Disruption time, to such collegeners as wanted a cheap diet and a respectable hame.’

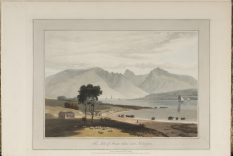

So spaiks Martha Spreull, the eponymous single wumman an douce laundleddy tae divinity scholarts frae the Glesga College at the Bell o the Brae. Martha’s warld is a series o ferrly hermless pliskies that tak place aroond Glesga toon an taks her on carrants tae a hydropathic institution an tae the Isle o Arran. Martha’s vocabulary, which maks up the first-person narrative o the novella, is rowthie in Scots. The Glesga patter o the present day prevails wi its big yins, auldyins, breengers an heid-the-baws, tho ‘Martha Spreull’ serves tae shaw that a nummer o Scots wirds hae disappeart frae the Glesga tung, sic as:

- muckle – large

- flett – floor of a house

- doonricht – downright

- nieves – fists

- jalouse – surmise

- cadger – beggar

- meddlet – meddled

- callant – young man

John Galt’s novel ‘The Entail’, imprentit in 1822 gies some kythin tae the yaise o braid Scots in earlier Glesga speech, as fir example here in the wirds o Provost Gorbals’ wife, Mrs Gorbals:

‘Eh! Megsty, gudeman, if I dinna think yon’s auld Kittlestonheugh’s crookit bairnswoman. I won’er whats come o the Laird, poor bodie, sin’ he was rookit by the Darien. Eh! what an alteration it was to Mrs Walkinshaw, his gudedochter. She was a bonny bodie, but frae the time o the sore news, she croynt awa, and her life gied out like the snuff o’ a can’le.’

‘The Entail’, Galt’s novel o covetousness an obsession, laudit bi Sir Walter Scott an Lord Byron, wis comparit wi Dostoevsky an Balzac an reckont tae be Galt’s finest wark. Galt’s novels wir aften parochial in settin whiles warldly in theme. ‘The Entail’ is set ower the coorse o the 18th century. The social staundin o its chairacters are reflectit in ther speech, a device yaised tae great effeck tae tell the tale. While baith the ‘gentle’ an professional classes speak in English, Scots is the medium gien tae a braider cast o the story an tae three o its principal chairacters, tho ‘the Leddy’, as ane o the gentry, is alsae gien a rowthie Scots vyce. The Leddy’s speech aiblins reflecks the comments made in Dean Ramsay’s ‘Reminiscences of Scottish Life and Character’, first imprentit in 1857, in which he notes:

‘I recollect old Scottish ladies and gentlemen who really spoke Scotch. It was not, mark me, speaking English with an accent. No; it was downright Scotch. Every tone and every syllable was Scotch.’

Gin the metropolitan classes had ettled tae lose ther ‘rough and uncouth brogue’ (the Scots leid as it wis in the estimation o Samuel Johnson), the lave o the population apparently still reteened a halesome Scots vocabulary. This can be seen in Glesga in the warks o 19th century Radical poets sic as Alexander Rodger, as weel as in novels (maistly throu dialogue) an plays ower mair than a hunder year syne the publication o Martha Spreull. In 1899, houanivir, Neil Munro, best-kent for his ‘Parahandy Tales’, scrieves in an airticle cried ‘Braid Scots’ anent the unsiccar set o the Scots tung.

‘But – one confesses the dreadful truth with reluctance – Braid Scots is a decaying tongue. It survives in the rural districts among the older people. In our own immediate neighbourhood a fine rich fruity Scots is still to be heard about East Kilbride; it comes over the moors (and yet has the tang of Burns) from Ayrshire. Paisley vaingloriously brags of speaking a fine brand of Scots, but I must confess I prefer it a little more dulcet than prevails in Seestu. Greenock also affects (I have heard it in her Town Council) a robust and classic vernacular, but I have studied her West Blackhall Street on a Saturday night and will kindly draw a veil. No, the dire truth cannot be concealed…in school, in church, in office, in warehouse, in the home and in the football field we are surrendering our proud Caledonian privilege of rolling our ‘r’s, and prolonging our vowels, and multiplying our gutturals.’

Munro then maks the case as tae how buiks are bein excised o Scots wirds fir the guid o publishers’ ‘genteel’ clients, an hou schuil buiks wi traditional Scots rhymes are likeweys bein Anglicised, no bi English but by Scottish publishers. The essayist furder scrieves on hou Scots is dauntened in edication:

‘Teachers insist that the English of the school-book and of the school hours shall be carried into the playground, and a boy of ten in a Renfrewshire school tells me he was severely reprimanded by his teacher for using the delightful word ‘ettled’ in his Sunday School class. The Sunday School teacher, a fastidious lady, had reported the lapse to the day school teacher and trouble ensued.’

Gin Munro haes a pynt wi regairds the insidious erosion o Scots, aiblins his concludin sentence wis ultimately wide aff the merk:

‘All this portends that before many generations the only Scotsmen who speak their native tongue will be in London’, jaloused tae mean that the Scots leid will be preserred in linguistic aspic ainly bi weel-intentioned if misguidit exiles. Whit Neil Munro micht think o the Scots leid an its 21st century dialecks is difficult tae faddom. Aiblins it can be jaloused that language an hou it evolves is a fykie maitter tae predict.

The Glesga novel o the 20th century wid become notit fir social realism, meanin that whiles the narrative wis in English, convincin chairacter roles cuid ainly be played oot bi speakin in ther authentic dialeck – or the nearest thing tae it. Irish author Patrick MacGill’s 1915 novel ‘The Rat Pit’, scrievit in English, wis a brutal expose o poverty an prostitution amang the sweat-shoaps an rack-rentit Glesga slums. In 1923 Greenock’s George Blake scrievit his first novel ‘Mince Collop Close’, a story o the Glesga slums an lassie gang-leader Bella MacFadyen, Queen of the Fan Tans.

West Central Scots wis nou becomin kent, in fiction at least, as haein its place amang the underclass. George Blake’s best-kent novel ‘The Shipbuilders’, set amang economic depression an industrial decline, wis imprentit in 1935, the same year as Long an MacArthur’s sensationalist novel ‘No Mean City’, the story o Glesga razor king Jonnie Stark. John McNeillie’s ‘Wigtown Ploughman: Part of His Life’, imprentit in 1939, wis set in the Machars o Wigtownshire an shawed impoverished life in rural Gallowa throu graphic depictions o haurdship an domestic violence. ‘Wigtown Ploughman’ caused a stushie when it wis first serialised in the The Daily Record then eftir imprentit as a novel. McNeillie follaed this a year later wi his saicent novel, ‘Glasgow Keelie’.

‘Glasgow Keelie’ is a coorse tale o urban violence an depravity. It bides in a thinly guised Glesga kent as Clydegate, wi South Clydegate its thinly guised Gorbals. The heid chairacter is Jimmie Lunn, a teenage rochian an ne’er-dae-weel wha has gan tae the city tae bide wi his auntie an uncle, an whaur he has fawn intae wrang weys. Clydegate is a daurk, rain-soaked dystopia whaur antihero Lunn bides in awe o his American screen idols George Raft an Edward G Robinson. Lunn’s descent intae ned-like tendencies sees him muivin frae the semi-respectable north side tae the sooth-side’s Beadle’s Place, a manky tenement hole o multiple deprivation whase unemployed denizens live oot a creeminal existence o skaith, thievery, alchyism an prostitution. Ben this hell-hole Lunn biggs up his young team, settin oot oan a series o joy-rides, smash-an-grab raids, protection racketeerin an ultra-violent square-goes wi the rival Chapel Row gang.

In MacNeillie’s sensationalist novel, the existence o this doontrodden unnerbelly is lichtened ainly bi veesits tae the local dance halls, picture-hooses, wrestlin halls an hote-pea shops, aw o which Lunn ettles throu extreme violence tae bring intae the grup o his creeminal empire. In moments o reflection, when Lunn isn’ae preoccupied wi his nefarious plans, or the attentions o his burd Jess, hirsel compromised bi her former life as a common huir, he is frichtened bi his ain capacity tae ‘think’, as ‘Glasgow Keelie’ spirals taewards its inevitable wanhappy conclusion.

Aw o whit seems a warld remuived frae the couthy Glesga o Martha Spreull. The post-war Glesga novel wid be exemplified bi Archie Hind’s ‘The Dear Green Place’. Set in the 1950s the novel tells the story o Matt Craig, a slauchter-hoose warker wha strauchles tae become a novelist. Paradoxically, the Glesga dialect that colours the pages o ‘The Dear Green Place’ is renunced bi Craig as a ‘…language cast out of jeers and violence and diffidence; a language of vulgar keelie scepticism.’

It wis a similar dingin-doon o the warkin class Glesga dialect – an its latter day propensity fir liberal yaise o the f-word – that wid lead tae controversy ower James Kelman’s 1994 Man Booker Prize-winnin novel ‘How Late It Was How Late’, endin in a flytin atween author an the British literary elite. Ane panellist threatened tae resign gin Kelman’s buik wis gied the prize, an whiles mony considert ‘How Late It Was How Late’ tae be a braw wark o fiction, The Times descried it as ‘literary vandalism’. In his acceptance speech James Kelman said, ‘A fine line can exist between elitism and racism’…’On matters concerning language and culture, the distinction can sometimes cease to exist altogether.’

The Glesga ‘patois’ can be foond in a rowth o novels an plays, in the folk-sangs o Matt McGinn, Adam MacNaughton an Ewan MacVicar, in the poems o Liz Lochead an Tom Leonard, an in poems sic as Stephen Mulrine’s ‘The Coming of the Wee Malkies’. Anne Donovan’s novel ‘Buddha Da’, imprentit in 2003, tells the story o the transcendence o a Glesga hoose-penter, frae the darg o ivryday existence tae his discovery o Buddhism, an the effecks this has oan his faimily. Scrievit in a rowthie Glesga narative, throu the vyces o penter Jimmy an his wife an dochter, ‘Buddha Da’ wis shortlistit fir the 2003 Orange Prize an wis recipient o the 2003 Whitbread Award fir first novel.

The Scottish Corpus of Texts and Speech (SCOTS) at the University o Glesga is a projeck that hairsts current yaises o language in Scotland an hauds them fir the study o future generations. Throu the SCOTS projeck it is possible tae see nae ainly contemporary yaises o the Scots leid, but hou these will chynge throu ongaun influences as the leid adapts an evolves. Tae quo frae the website:

‘The Scottish Corpora project has created large electronic corpora of written and spoken texts for the languages of Scotland. The Scottish Corpus of Texts & Speech (SCOTS) has been online since November 2004, and, after a number of updates and additions, has reached a total of nearly 4.6 million words of text, with audio recordings to accompany many of the spoken texts. A sister resource, the Corpus of Modern Scottish Writing, was launched in 2010, and now comprises 5.4 million words of written text with accompanying images.

Together, the Scottish corpora allow those interested in Scotland’s linguistic diversity, and in Scottish culture and identity, to investigate the languages of Scotland in new ways, and to address the gap which presently exists in our knowledge of these. The resources also preserve information on these languages for future generations.’

‘Martha Spreull, Being Chapters in the Life of a Single Wumman’, published in 1887 is a light-hearted and jovial novella set in Glasgow and written in broad Scots. It was written by Henry Johnston under the pseudonym Zachary Fleming. Johnston’s collected sketches of Martha Spreull were originally serialised in a publication called ‘Quiz.’

Johnston was born in Northern Ireland and his family would move to Glasgow when he was three years old. He would spend the remainder of his days in Glasgow and become a familiar figure in public life, being one of the original members of the Glasgow Ballad Club and serving as its President. He became known as author of a handful of novels in the kailyard tradition and was compared with writers such as George MacDonald an JM Barrie. His novels included ‘The Chronicles of Glenbuckie’. Like the earlier novels of Galt and Scott these would use English narrative with character voices in Scots. ‘Martha Spreull’, with the exception of an introduction and closing note by the editor, is written entirely in Scots an gives some demonstration of Glasgow speech towards the end of the 19th century.

In contrast to the agreeable tones of Martha Spreull, the Glasgow novel of the following modern period by writers such as Patrick MacGill, John McNeillie and George Blake, as well as plays such as Ena Lamont Stewart’s ‘Men Should Weep’- with themes of violence, exploitation and poverty – would show the darker aspects of Glasgow life. Through the voices of their characters, these literary and dramatic works, among many others, demonstrate linguistic shifts in the Scots tongue over a period of time.

Learn more about Martha Spreull an Glesga Scots

‘I am real muckle fashed wi’ my head, especially when I get a waff o’ cauld; and since I wrote last I have had a wonnerfu’ sair brash, which accounts, in pairt, for my backwardness in beginning this chapter. I have already tell’d ye hoo my interest in the higher forms o edication began by the opening o my flett o rooms, efter the Disruption time, to such collegeners as wanted a cheap diet and a respectable hame.’

So speaks Martha Spreull, the eponymous ‘single wumman’ and respectable landlady to divinity students from the Glasgow College at the Bell o the Brae. Martha’s world is a series of fairly harmless escapades that take place around the town of Glasgow and takes her on jaunts to a hydropathic institution and to the Isle of Arran. Martha’s vocabulary, which makes up the first-person narrative of the novella, is rich in Scots. The ‘Glesga patter’ of the present day prevails with its big yins, auldyins, breengers and heid-the-baws, though ‘Martha Spreull’ serves to show that a number of Scots words have disappeared from the Glasgow tongue, such as:

- muckle – large

- flett – floor of a house

- doonricht – downright

- nieves – fists

- jalouse – surmise

- cadger – beggar

- meddlet – meddled

- callant – young man

John Galt’s novel ‘The Entail’, published in 1822 gives some demonstration of the use of braid Scots in earlier Glasgow speech, as for example here in the words of Provost Gorbals’ wife, Mrs Gorbals:

‘Eh! Megsty, gudeman, if I dinna think yon’s auld Kittlestonheugh’s crookit bairnswoman. I won’er whats come o the Laird, poor bodie, sin’ he was rookit by the Darien. Eh! what an alteration it was to Mrs Walkinshaw, his gudedochter. She was a bonny bodie, but frae the time o the sore news, she croynt awa, and her life gied out like the snuff o’ a can’le.’

‘The Entail’, Galt’s novel of covetousness and obsession, lauded by Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron, was compared with Dostoevsky and Balzac and reckoned to be Galt’s finest work. Galt’s novels were often parochial in setting while worldly in theme. ‘The Entail’ is set over the course of the eighteenth century. The social standing of its characters are reflected in their speech, a device used to great effect to tell the tale. While both the ‘gentle’ and professional classes speak in English, Scots is the medium given to a wider cast of the story and to three of its principal characters, though ‘the Leddy’, as one of the gentry, is also given a rich Scots voice. The Leddy’s speech perhaps reflects the comments made in Dean Ramsay’s ‘Reminiscences of Scottish Life and Character’, first published in 1857, in which he notes:

‘I recollect old Scottish ladies and gentlemen who really spoke Scotch. It was not, mark me, speaking English with an accent. No; it was downright Scotch. Every tone and every syllable was Scotch.’

If the metropolitan classes had resolved to lose their ‘rough and uncouth brogue’ (the Scots language as it was in the estimation of Samuel Johnson), the majority of the population apparently still retained a wholesome Scots vocabulary. This can be seen in Glasgow among the works of 19th century Radical poets such as Alexander Rodger and in novels (mostly through dialogue) and plays over more than a hundred years since the publication of Martha Spreull. In 1899, however, Neil Munro, best-known for his ‘Parahandy Tales’, in an article called ‘Braid Scots’ writes about the precarious state of the Scots tongue.

‘But – one confesses the dreadful truth with reluctance – Braid Scots is a decaying tongue. It survives in the rural districts among the older people. In our own immediate neighbourhood a fine rich fruity Scots is still to be heard about East Kilbride; it comes over the moors (and yet has the tang of Burns) from Ayrshire. Paisley vaingloriously brags of speaking a fine brand of Scots, but I must confess I prefer it a little more dulcet than prevails in Seestu. Greenock also affects (I have heard it in her Town Council) a robust and classic vernacular, but I have studied her West Blackhall Street on a Saturday night and will kindly draw a veil. No, the dire truth cannot be concealed…in school, in church, in office, in warehouse, in the home and in the football field we are surrendering our proud Caledonian privilege of rolling our ‘r’s, and prolonging our vowels, and multiplying our gutturals.’

Munro then makes the case as to how books are being excised of Scots words for the good of publishers’ ‘genteel’ clients, and how school books with traditional Scots rhymes are likewise being Anglicised, not by English but by Scottish publishers. The essayist further writes on how Scots is discouraged in education:

‘Teachers insist that the English of the school-book and of the school hours shall be carried into the playground, and a boy of ten in a Renfrewshire school tells me he was severely reprimanded by his teacher for using the delightful word ‘ettled’ in his Sunday School class. The Sunday School teacher, a fastidious lady, had reported the lapse to the day school teacher and trouble ensued.’

If Munro has a point with regards the insidious erosion of Scots, possibly his concluding sentence was ultimately wide of the mark:

‘All this portends that before many generations the only Scotsmen who speak their native tongue will be in London’, taken to mean that the Scots language will be preserved in linguistic aspic only by well-intentioned if misguided exiles. What Neil Munro might think of the Scots language and its 21st century dialects is difficult to fathom. Perhaps it can be surmised that language and how it evolves is a fickle matter to predict.

The Glasgow novel of the 20th century would become noted for social realism, meaning that while the main narrative was in English, convincing character roles could only be played out by speaking in their authentic dialect – or the nearest thing approaching it. Irish author Patrick MacGill’s 1915 novel ‘The Rat Pit’, written in English, was a brutal expose of poverty and prostitution among the sweat-shops and rack-rented Glasgow slums. In 1923 Greenock’s George Blake wrote his first novel ‘Mince Collop Close’, a story of the Glasgow slums and girl gang-leader Bella MacFadyen, Queen of the Fan Tans.

West Central Scots was now becoming recognised, in fiction at least, as having its place among the underclass. George Blake’s best-known novel ‘The Shipbuilders’, set amid economic depression and industrial decline, was published in 1935, the same year as Long and MacArthur’s sensationalist novel ‘No Mean City’, the story of Glasgow razor king Jonnie Stark. John McNeillie’s ‘Wigtown Ploughman: Part of His Life’, published in 1939, was set in the Machars of Wigtownshire and showed impoverished life in rural Galloway through graphic depictions of hardship and domestic violence. ‘Wigtown Ploughman’ caused a furore when it was first serialised in the The Daily Record and subsequently published as a novel. McNeillie followed this a year later with his second novel, ‘Glasgow Keelie’.

‘Glasgow Keelie’ is a squalid tale of urban violence and depravity. Its world is a thinly disguised Glasgow known as Clydegate, with South Clydegate its thinly disguised Gorbals. Its protagonist is Jimmie Lunn, a teenage ruffian and ne’er-do-well who has gone to the city to live with his aunt and uncle, and where he has fallen into delinquent habits. Clydegate is a dark, rain-soaked dystopia where antihero Lunn lives in awe of his American screen idols George Raft and Edward G Robinson. Lunn’s descent into delinquency sees him moving from the semi-respectable north side to the south-side’s Beadle’s Place, a filth-strewn tenement sink of multiple deprivation whose unemployed denizens live out a criminal existence of violence, thievery, alcoholism and prostitution. Within this hell-hole Lunn raises up his youthful gang, setting out on a series of joy-rides, smash-and-grab raids, protection racketeering and ultra-violent confrontation with the rival Chapel Row gang.

In MacNeillie’s sensationalist novel, the existence of this downtrodden underbelly is lightened only by visits to the local dance halls, cinemas, wrestling halls and hot-pea shops, all of which Lunn strives through extreme violence to bring under the control of his criminal empire. In moments of reflection, when Lunn isn’t preoccupied with his nefarious plans, or the attentions of his girlfriend Jess, herself compromised by her former life as a common prostitute, he is disturbed by his own capacity to ‘think’, as ‘Glasgow Keelie’ spirals towards its inevitable unhappy conclusion.

All of which seems a world removed from the comforting world of Martha Spreull. The post-war Glasgow novel would be exemplified by Archie Hind’s ‘The Dear Green Place’. Set in the 1950s the novel tells the story of Matt Craig, a slaughter-house worker who struggles to become a novelist. Paradoxically, the Glasgow dialect which colours the pages of ‘The Dear Green Place’ is renounced by Craig as a ‘…language cast out of jeers and violence and diffidence; a language of vulgar keelie scepticism.’

It was a similar denouncement of the working class Glasgow dialect – and its latter-day propensity for liberal use of the f-word – that would lead to controversy over James Kelman’s 1994 Man Booker Prize-winning novel ‘How Late It Was How Late’, ending in a feisty confrontation between author and the British literary elite. One panellist threatened to resign if Kelman’s book was given the prize, and while many considered ‘How Late It Was How Late’ to be an excellent work of fiction, The Times decried it as ‘literary vandalism’. In his acceptance speech James Kelman said, ‘A fine line can exist between elitism and racism’…’On matters concerning language and culture, the distinction can sometimes cease to exist altogether.’

The Glasgow ‘patois’ can be found in a number of novels and plays, in the folk-songs of Matt McGinn, Adam MacNaughton and Ewan MacVicar, in the poems of Liz Lochead and Tom Leonard, and in poems like Stephen Mulrine’s ‘The Coming of the Wee Malkies’. Anne Donovan’s novel ‘Buddha Da’, published in 2003, tells the story of the transcendence of a Glasgow house painter from the toil of everday existence to his discovery of Buddhism, and the effects this has on his family. Written in a rich Glaswegian narative, through the voices of painter Jimmy and his wife and daughter, ‘Buddha Da’ was shortlisted for the 2003 Orange Prize and was recipient of the 2003 Whitbread Award for first novel.

The Scottish Corpus of Texts and Speech (SCOTS) at the University of Glasgow is a project that collects current uses of language in Scotland and holds them for the study of future generations. Through the SCOTS project it is possible to see not only contemporary uses of the Scots language, but how these will change through on-going influences as language adapts and evolves. To quote from the website:

‘The Scottish Corpora project has created large electronic corpora of written and spoken texts for the languages of Scotland. The Scottish Corpus of Texts & Speech (SCOTS) has been online since November 2004, and, after a number of updates and additions, has reached a total of nearly 4.6 million words of text, with audio recordings to accompany many of the spoken texts. A sister resource, the Corpus of Modern Scottish Writing, was launched in 2010, and now comprises 5.4 million words of written text with accompanying images.

Together, the Scottish corpora allow those interested in Scotland’s linguistic diversity, and in Scottish culture and identity, to investigate the languages of Scotland in new ways, and to address the gap which presently exists in our knowledge of these. The resources also preserve information on these languages for future generations.’

- Author:

- Henry Johnston

- Publication Date:

- 1887

- Imprentit:

Glasgow

Martha Spreull

‘I was mortal angry, as ye may jalouse, when Maister Fleming, the writer, telt me that the College authorities wud hae naething a dae wi the bursary I had set my heart on givin’ to the best first year’s student who should compete for it. The bursary, as ye’ll nae doot recollect, wis to be tenable for four years.’

Frae Martha Spreull