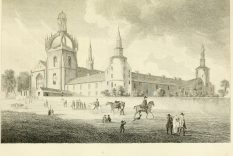

Anna Gordon wis born in 1747 in Auld Aiberdeen whaur her faither Thomas Gordon wis professor o humanity an Greek at King’s College. Thomas Gordon’s grandson Robert Eden Scott wid become professor o moral philosophy at Kings College. These twa men played heid roles in university life, haein served as College Regent. Baith wir gleg contributors tae the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, a body kent fir gien a hantle o significant warks tae the Scottish Enlightenment.

Like ither pairts o Scotland, ballads at that time wir susteened throu the oral tradition an in prent bi circulation o popular broadsides an chap-buiks. Aunts, nurses an auldwives frae upper Deeside wir said in a letter scrievit bi Professor Thomas Gordon tae hae been the springheid o Anna’s ballad collection.

In 1788 Anna Gordon mairrit the Rev Dr Andrew Brown, meenister o Falkland, syne becomin kent as Mrs Brown of Falkland. She returned tae Aiberdeen in later life whaur she deed in 1810 an wis yirdit at St Machar’s Cathedral near tae King’s College in Auld Aiberdeen.

Lear mair aboot The ballads o Anna Gordon Brown

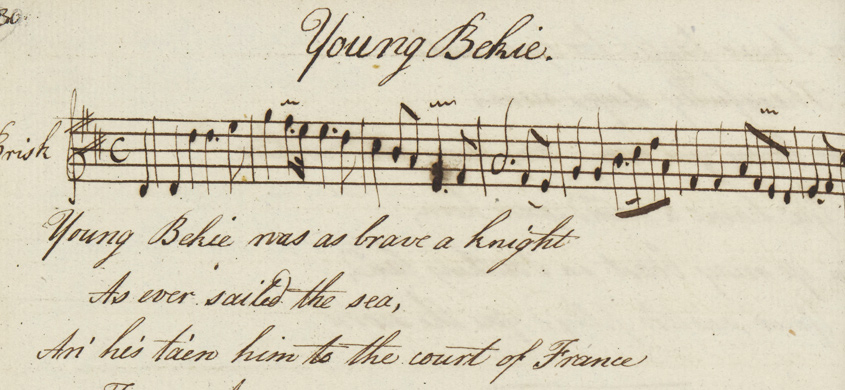

Some time afore 1783 Robert Eden Scott had scrievit doon aroond 20 ballads frae Anna Gordon’s singin. It wis bi mention o his dochter’s repertoire tae associate William Tytler, a noted Scottish advocate an historian, that Thomas Gordon ettled tae hae mair ballads recordit fir Tytler’s scrutiny. Fifteen ballads wir syne scrievit doon frae Anna’s singin, wi Robert gien musical notations fir the melodies.

In 1800 Anna scrievit doon a furder nine ballads in her ain haund, this time withoot musical notation. It is these twa original manuscripts conteenin a total o 24 ballads that are held in lang-term deposit at the National Leebrar o Scotland. Baith are prefaced bi contemporary letters which expone the origins o the ballads. The Leebrar also hauds copies o the twa volumes o Robert Jamieson’s ‘Popular ballads and songs’ which include five ballads frae Anna Gordon Brown’s repertoire. The Leebrar also hauds a copy o ‘The ballad repertoire of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown of Falkland’, editit bi Sigrid Rieuwerts an imprentit bi the Scottish Texts Society in 2011. This imprent gies braw insicht intae the haill Anna Gordon corpus.

The ballad repertoire o Anna Gordon Brown, forby it haes whiles dividit scholarly opinion on maitters o origin an interpretation, wis commendit bi leadin warld folklorist Francis James Child o Harvard University, editor o the definitive ‘The English and Scottish popular ballads’ (1882-1898). In Child’s ain words:

‘There are no ballads superior to those sung by Mrs Brown of Falkland in the last century.’

Ballads are ancient survivors o the oral Scottish tradition an are thocht tae hae sprung frae a yet aulder tradition o epic poetry an storytellin. They maist likely sprung tae popularity in the medieval period an hae coonterpairts ootthrou Britain an Europe. In its maist basic form, a ballad is a story tauld in sang whaur a protagonists relates the scenes o the tale in a straucht an unaffectit manner. Weel kent Scottish ballads are ‘Sir Patrick Spens’, ‘The Dowie Dens of Yarrow’ an ‘the Wife of Usher’s Well’. A ballad in its richt sense will be an anonymous wark rootit in these traditions. It will be ordinarily be sung unaccompanit, raither than be a recent folk or contemporary sang wi kent authorship.

The Medieval ballad is variously said tae hae its origins throu the repertoire o traivellin bairds, in the sangs o monks durin leisure oors or amang fowk at the workplace. Scottish ballads wir susteened richt up tae modren times bi the traditions o the traivellin gypsy clans kent as ‘tinkers’ or ‘tinklers’.

The advent o prent wid see ballads become popularised throu illustratit broadsides, aftimes re-prentit in variant or mixter-maxter versions. They wid become furder popularised throu prentit bukes wi the editorship o the likes o Robert Jamieson, Thomas Percy, Walter Scott, James Hogg, David Herd, William Motherwell an James Francis Child – featurin in imprents sic as Percy’s ‘The reliques of ancient English poetry’, Scott’s ‘Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border’, Motherwell’s ‘The Harp of Renfrewshire’ an James Johnson’s ‘Scots musical museum’.

Prentit ballads wir in some weys problematic in that the sentiment wis aiblins compromised due tae the absence o music an aural experience. An editor micht alsae be temptit tae add a verse or chynge a line tae ‘improve’ a ballad fir dramatic purposes or metrical sense. This wid inadvertently tak the hert oot o the piece in the process. As is seen in Professor Thomas Gordon’s letter tae Alexander Tytler o 19 January 1793, he appears in nae doot as tae the provenance an authenticity o his dochter’s ballad repertoire:

‘An aunt of my children (Mrs Farquherson now dead) who was married to the proprietor of a small estate near the sources of the Dee in Braemar, a good old woman who spent the best part of her working life among flocks and herds resided in her later days in the town of Aberdeen. Being maternally fond of my children, when young she had them much about her and delighted them with her songs & tales of chivalry. My youngest daughter Mrs Brown of Falkland is blessed with a memory as good as her aunt and has almost the whole store of her songs by heart.’

Whit micht may be debatable is hou faithfully a ballad wis reteened atween the sangster’s rendition an transition tae page – an whither frae a linguistic pynt o view certain wirds micht hae been assimilated tae a mair staundardised English. Thair appear tae be occasions whaur a line micht hae been chynged tae accommodate an Anglified form o spellin. Fir exaumple in the version o ‘Burd Ellen’ in Robert Jamieson’s ‘Popular Ballads and Songs’:

‘O, tell me this now, my good lord John,

In pity tell to me,*

How far it is to your lodgin,

Whare we this night maun be?’

* Jamieson notes that this line replaces the original ‘And a word you dinna lie’, but it is jaloused here that in order tae be consistent in rhyme, the original line is mair likely tae hae been in Scots – ‘And a word you dinna lee.’

Ther are alsae variations in spellins sic as ‘mother’ an ‘mither’, ‘yellow’ an ‘yallow’.

The survivin Anna Gordon Brown ballad collection is classified intil five manuscripts, kent as Brown A, B, C, D or E.

Brown A conseests o 20 ballads originally scrievit doon bi Robert Eden Scott some time afore 1783, an wis copied oot in the haund o Robert Jamieson in 1799. This manuscript is haudit in the David Laing Collection in the University o Edinburgh Leebrar.

Brown B conseests o 15 ballads scrievit doon bi the haund o Robert Eden Scott in 1783, gien musical notations tae the melodies.

Brown C conseests o nine ballads scrievit in Anna Gordon Brown’s haund in 1800 and daesna include musical notation.

Brown D is a collection o fower letters tae Robert Jamieson dated 1800-1805 an includes three ballads scrievit doon bi the haund o Andrew Brown.

Brown E is a prentit source an conteens five ballads which appear in Robert Jamieson’s 1806 ‘Popular ballads and songs’, Volumes 1 and 2.

It is the boond manuscripts kent as ‘Brown B’ an ‘Brown C’ which are held in lang-term deposit at the Naitional Leebrar , wi contents as follaes:

Brown B

- Willie’s Lady

- Clark Colven

- Brown Adam

- Little Jack the Scot

- Chil’ Brenton

- The Grey Goshawk

- Young Bekie

- Rose the Red and White Lily

- Brown Robin

- Willie o’ Douglas Dale

- Kempion

- Lady Elspat

- King Henry

- Lady Maisery

- Her Cruel Sister

Brown C

- Thomas the Rhymer & Queen of Elfland

- Love Gregor

- Fa’se Footrage

- Jellon Grame and Lillie Flower.

- The Bonny Earl of Livingstone

- Bonnie Bee’hom

- Bonnie Foot-boy

- Cruel Brother, or the Bride’s Testament

- Lord John & Burd Ellen

Wi respeck tae ‘Brown E’, the Naitional Leebrar hauds the 2 Volumes o Robert Jamieson’s ‘Popular ballads and songs’ which include the follaein frae the Anna Gordon Brown repertoire.

Volume 1

. Burd Ellen – p. 113

. Willie & May Margaret – p.135

. Hugh of Lincoln – p. 139

. Lamikin – p. 176

Volume 2

. The Birth of Robin Hood – p.44

In ‘The ballad repertoire of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown of Falkland’, Sigrid Rieuwerts gies an accoont as tae hou the Brown B an Brown C manuscripts, eventually comin unner custodianship o the Fraser-Tytler family at Aldourie Castle on south Loch Ness, became lost fir pairt o the 19th an 20th centuries. Aroond 1927 the Brown C manuscript wis discovert bi Mrs Christian Fraser-Tytler in a safe in the wine-cellar at Aldourie Castle. Some time in the 1930s she discovert Brown B on the tapmaist shelf o the library, as she later recalled, ‘bound in with a lot of pamphlets and papers’.

Anna Gordon Brown’s ballads are fouthie in mystery an skaith. In ‘Willie’s Lady’ a vengefu mither ettles tae kill her son’s bride an unborn bairn throu her pooers o witchcraft. In the end it is Willie wha, on the rede o his Lady, yaises the black airts tae turn the situation in thair favour:

‘Ye do ye to the market place,

And there ye buy a loaf o wax,

You shape it, bairn & bairnly like,

An in twa glassen een you pit…’

Willy finally undoes the witchcraft bi loosenin ‘the nine witch knots/that was amo’ his lady’s locks.’

In ‘Clark Colven’ the protagonist hechts lealty tae his lover but is seduced bi a marmaiden in a river. Whan he suffers gruesome heid pains the marmaiden plays cantrips oan him bi sayin he will find a cure bi cuttin a strip frae her sleeve an rowin it aroond his heid. This haes fatal consequences as she chynges aince again tae a fish an taks tae the stream whiles Clark Colven slips taewards daith:

‘O mither, mither mak my bed,

An gentle Lady lay me down;

O brither, brither unbend my bow,

Twill never be bent by me again.’

In ‘Brown Adam’ a fause knicht attempts tae seduce Brown Adam’s lover bi wysin her wi riches:

‘Out he has tae’n a purse o goud,

Was a’ fu to the string

“Grant me but love for love, Lady,

An a’ this shall be thine.’

Whan she refuses his walth he finally threatens her wi daith at whit pynt Brown Adam arrives an cuts fower fingers frae the richt haund o the fause knicht.

In the ‘Brown C’ manuscript Mrs Brown offers an introduction tae ‘Thomas the Rhymer & Queen of Elfland’, a ballad also kent as ‘Tam Lin’ or ‘Tamlane’;

‘The tradition concerning this ballad is that Thomas Rhymer when young, was carried away by the Queen of Elfland or Fairlyland; who retained him in her service for seven years, during which period he is supposed to have acquired that wisdom which afterwards made him so famous.’

Here she refers tae Tammas the Rhymer or Tammas o Ercildoune, a 13th century worthie wha reputedly had the gift o prophecy. An accoont o Tammas appears in Hector Boece’s 1527 Latin ‘Chronicles of Scotland’, syne owerset intae Scots bi John Bellenden an imprentit in 1536. ‘Tam Lin’ in its various forms haes been imprentit amang ithers bi Robert Burns an Walter Scott. It wis referenced in 1549 polemic ‘The Complaynt of Scotland’ which drew on the strynths o Scotland’s traditions. A version o ‘Tam Lin’ alsae appears in Duncan Williamson’s ‘A thorn in the King’s foot; Stories of the Scottish Travelling People’(1987).

Keepit ower centuries throu the traditions o Scotland’s traivellin fowk, the ballad tradition unnerwent an unexpectit revival in the post-war years, whan folklorists sic as Hamish Henderson an Alan Lomax ettled tae record fir the common-weel whit had bidit o Scotland’s oral traditions. In Suzanne Gilbert’s article ‘Scottish ballads and popular culture’, imprentit in the Association of Scottish Literary Studies e-zine ‘The Bottle Imp’ Issue 5 May 2009, she scrieves,

‘The most influential collector, Hamish Henderson (1919-2002), camped out in the Perthshire berry fields, tapping into a rich stream of traditional ballads preserved among the travelling families of Perthshire and Fife – singers such as Jeannie Robertson, Belle Stewart, and Betsy Whyte, who became internationally renowned. Recording the songs for Edinburgh’s School of Scottish Studies, which he co-founded, Henderson reported that it “was like holding a bucket under Niagra Falls”.’

The ballad tradition wid fire up the 1950s an 60s folk music revivals, throu sangsters sic as Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Jean Redpath an The Watersons. It continues tae haud swey amang folk musicians o the present day, in the sangs an music o sic as the Battlefield Band, Karine Polwart, an Old Blind Dogs.

Versions o ‘Tam Lin’ hae been recordit bi many folk artists includin Fairport Convention, Pentangle, an Steeleye Span. ‘The Ballad of Tam Lin’ or ‘The Devil’s Widow’, a contemporary re-tellin o the ancient Scottish ballad, is a 1970 horror film directit bi Roddy McDowall an featurin Ava Gardner an Ian McShane.

Anna Gordon was born in 1747 in Old Aberdeen where her father Thomas Gordon was professor of humanity and Greek at King’s College. Thomas Gordon’s grandson Robert Eden Scott became professor of moral philosophy at King’s College. These two men played leading roles in university life, having served as College Regent. Both were active contributors to the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, a body attributed with providing a quantity of significant works to the Scottish Enlightenment.

Like other parts of Scotland, ballads at that time were sustained through the oral tradition and in print by circulation of popular broadsides and chap-books. Aunts, nurses and old women from upper Deeside were said in a letter by Thomas Gordon to have been the wellspring of Anna’s ballad collection.

In 1788 Anna Gordon married the Rev Dr Andrew Brown, minister of Falkland, thereafter becoming known as Mrs Brown of Falkland. She returned to Aberdeen where she died in 1810 and was buried at St Machar’s Cathedral near to King’s College in Old Aberdeen.

Learn more about The ballads o Anna Gordon Brown

At some time before 1783 Robert Eden Scott had written down around 20 ballads from Anna’s singing. It was through mention of his daughter’s repertoire to associate William Tytler, a noted Scottish advocate and historian, that Thomas Gordon was motivated to have more ballads recorded for Tytler’s scrutiny. Fifteen ballads were thereafter written down from Anna’s singin, with Robert giving musical notations for the melodies.

In 1800 Anna wrote down a further nine ballads in her own hand, this time without musical notation. It is these two original manuscripts containing a total of 24 ballads that are held on long-term deposit at the National Library of Scotland. Both are prefaced by contemporary letters which explain the origins of the ballads. The Library also holds copies of the two volumes of Robert Jamieson’s ‘Popular nallads and songs’ which include five ballads from Anna Gordon Brown’s repertoire. The library also holds a copy of ‘The ballad repertoire of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown of Falkland’ edited by Sigrid Rieuwerts and published by the Scottish Texts Society in 2011. This publication gives excellent insight into the whole Anna Gordon corpus.

The ballad repertoire of Anna Gordon Brown, notwithstanding that it has occasionally divided scholarly opinion on questions of origin and interpretation, was commended by world folklorist Francis James Child of Harvard University, editor of the definitive ‘The English and Scottish popular ballads’ (1882-1898). In Child’s own words:

‘There are no ballads superior to those sung by Mrs Brown of Falkland in the last century.’

Ballads are ancient survivors of the oral Scottish tradition and are believed to have sprung from a yet older tradition of epic poetry and storytelling. They most likely rose to popularity in the medieval period and have counterparts throughout Britain and Europe. In its most basic form a ballad is a story told in song where a protagonist relates the scenes of a tale in a direct and unaffected manner. Well known Scottish ballads are ‘Sir Patrick Spens’, ‘The Dowie Dens of Yarrow’ and ‘the Wife of Usher’s Well’. A ballad in its truest sense will be an anonymous work rooted in these traditions. It will normally be sung unaccompanied, rather than be a recent folk or contemporary song with known authorship.

The Medieval ballad is variously said to have its origins through the repertoire of travelling minstrels, in the songs of monks during leisure hours or among the common populace or at the workplace. Scottish ballads were sustained up until modern times by the traditions of the travelling gypsies known as ‘tinkers’ or ‘tinklers’’.

The advent of print would popularise ballads through illustrated broadsides, often re-printed in in variant or mixed versions. They would become further popularised through printed books with the editorship of such as Robert Jamieson, Thomas Percy, Walter Scott, James Hogg, David Herd, William Motherwell and James Francis Child – featuring in publications such as Percy’s ‘The reliques of ancient English poetry’, Scott’s ‘Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border’, Motherwell’s ‘The Harp of Renfrewshire’ and James Johnson’s ‘Scots musical museum’.

Printed ballads were in some ways problematic in that the sentiment was possibly compromised due to the absence of music and aural experience. An editor might also be tempted to add a verse or change a line to ‘improve’ a ballad for dramatic purposes or metrical sense, inadvertently removing the essence of the piece in the process. As seen in Professor Thomas Gordon’s letter to Alexander Tytler of 19 January 1793, he appears to be in no doubt as to the provenance and authenticity of his daughter’s ballad repertoire:

‘An aunt of my children (Mrs Farquherson now dead) who was married to the proprietor of a small estate near the sources of the Dee in Braemar, a good old woman who spent the best part of her working life among flocks and herds resided in her later days in the town of Aberdeen. Being maternally fond of my children, when young she had them much about her and delighted them with her songs & tales of chivalry. My youngest daughter Mrs Brown of Falkland is blessed with a memory as good as her aunt and has almost the whole store of her songs by heart.’

What might may be debatable is how faithfully a ballad was retained between the singer’s rendition and transition to page – and whether from a linguistic point of view certain words might have been assimilated to a more standardised English. There appear to be occasions where a line might have been altered to accommodate an Anglicised form of spelling. For example in the version of ‘Burd Ellen’ in Jamieson’s ‘Popular ballads and songs’:

‘O, tell me this now, my good lord John,

In pity tell to me,*

How far it is to your lodgin,

Whare we this night maun be?’

*Here Jamieson notes that this line replaces the original ‘And a word you dinna lie’, but it is conjectured that in order to be consistent in rhyme, the original line is more likely to have been in the Scots: ‘And a word you dinna lee‘.

There are also variations in spellings such as ‘mother’ and ‘mither’, ‘yellow’ and ‘yallow’.

The surviving Anna Gordon Brown ballad collection is classified into five manuscripts, known as Brown A, B, C, D or E.

Brown A consists of 20 ballads originally written down by Robert Eden Scott some time before 1783, and was copied out in the hand of Robert Jamieson in 1799. This manuscript is held in the David Laing Collection in the University of Edinburgh Library.

Brown B consists of 15 ballads written down by the hand of Robert Eden Scott in 1783, giving musical notations to the melodies.

Brown C consists of nine ballads written in Anna Gordon Brown’s hand in 1800 and does not include musical notation.

Brown D is a collection of four letters to Robert Jamieson dated 1800-1805 and includes three ballads written down by the hand of Andrew Brown.

Brown E is a printed source and contains five ballads which appear in Robert Jamieson’s 1806 ‘Popular ballads and songs’, Volumes 1 and 2.

It is the bound manuscripts known as ‘Brown B’ and ‘Brown C’ which are held in long-term deposit at the National Library, with contents as follows:

Brown B

- Willie’s Lady

- Clark Colven

- Brown Adam

- Little Jack the Scot

- Chil’ Brenton

- The Grey Goshawk

- Young Bekie

- Rose the Red and White Lily

- Brown Robin

- Willie o’ Douglas Dale

- Kempion

- Lady Elspat

- King Henry

- Lady Maisery

- Her Cruel Sister

Brown C

- Thomas the Rhymer & Queen of Elfland

- Love Gregor

- Fa’se Footrage

- Jellon Grame and Lillie Flower.

- The Bonny Earl of Livingstone

- Bonnie Bee’hom

- Bonnie Foot-boy

- Cruel Brother, or the Bride’s Testament

- Lord John & Burd Ellen

With respect to ‘Brown E’, the Library holds the 2 volumes of Robert Jamieson’s ‘Popular ballads and songs’ which include the following from the Anna Gordon Brown repertoire.

Volume 1

. Burd Ellen – p. 113

. Willie & May Margaret – p.135

. Hugh of Lincoln – p. 139

. Lamikin – p. 176

Volume 2

. The Birth of Robin Hood – p.44

In ‘The ballad repertoire of Anna Gordon, Mrs Brown of Falkland’, Sigrid Rieuwerts gives an account as to how the Brown B an Brown C manuscripts, eventually coming under custodianship of the Fraser-Tytler family at Aldourie Castle on south Loch Ness, became lost for part of the 19th and 20th centuries. Around 1927 the Brown C manuscript wis discovered by Mrs Christian Fraser-Tytler in a safe in the wine-cellar at Aldourie Castle. Some time in the 1930s she discovered Brown B on an upper shelf of the library, as she later recalled, ‘bound in with a lot of pamphlets an papers’.

Anna Gordon Brown’s ballads are abundant in mystery and violence. In ‘Willie’s Lady’ a vengeful mother resolves to kill her son’s bride and unborn child through her powers of witchcraft. In the end it is Willie who, on the counsel of his Lady, uses the black arts to turn the situation in their favour:

‘Ye do ye to the market place,

And there ye buy a loaf o wax,

You shape it, bairn & bairnly like,

An in twa glassen een you pit…’

Willy finally undoes the witchcraft by loosening ‘the nine witch knots/that was amo’ his lady’s locks.’

In ‘Clark Colven’ the protagonist pledges loyalty to his lover but is seduced by a mermaid in a river. When he suffers terrible head pains the mermaid enchants him by saying he will find a cure by cutting a strip from her sleeve and wrapping it around his head. This has fatal consequences as she transforms once again to a fish and takes to the stream while Clark Colven slips towards death:

‘O mither, mither mak my bed,

An gentle Lady lay me down;

O brither, brither unbend my bow,

Twill never be bent by me again.’

In ‘Brown Adam’ a false knight attempts to seduce Brown Adam’s lover by luring her with riches:

‘Out he has tae’n a purse o goud,

Was a’ fu to the string

“Grant me but love for love, Lady,

An a’ this shall be thine”.’

When she refuses his riches he finally threatens her with death at which Brown Adam arrives and cuts four fingers from the right hand of the false knight.

In the ‘Brown C’ manuscript Mrs Brown offers an introduction to ‘Thomas the Rhymer & Queen of Elfland’, a ballad also known as ‘Tam Lin’ or ‘Tamlane’:

‘The tradition concerning this ballad is that Thomas Rhymer when young, was carried away by the Queen of Elfland or Fairlyland; who retained him in her service for seven years, during which period he is supposed to have acquired that wisdom which afterwards made him so famous.’

Here she refers to Thomas the Rhymer or Thomas of Ercildoune, a 13th century real-life character reputedly having the gift of prophecy. An account of Thomas appears in Hector Boece’s 1527 Latin ‘Chronicles of Scotland’, subsequently translated into Scots by John Bellenden and published in 1536. ‘Tam Lin’ in its various forms has been published among others by Robert Burns and Walter Scott. It was referenced in 1549 polemic ‘The Complaynt of Scotland’ which drew on the strengths of Scotland’s traditions. A version of ‘Tam Lin’ appears in Duncan Williamson’s ‘A thorn in the King’s foot; Stories of the Scottish Travelling People’(1987).

Retained over centuries through the traditions of Scotland’s travelling people, the ballad tradition underwent an unexpected revival in the post-war years, when folklorists such as Hamish Henderson and Alan Lomax resolved to record for posterity that which had prevailed of Scotland’s oral traditions. In Suzanne Gilbert’s article ‘Scottish ballads and popular culture’, published in the Association of Scottish Literary Studies ezine ‘The Bottle Imp’ Issue 5 May 2009, she writes,

‘The most influential collector, Hamish Henderson (1919-2002), camped out in the Perthshire berry fields, tapping into a rich stream of traditional ballads preserved among the travelling families of Perthshire and Fife – singers such as Jeannie Robertson, Belle Stewart, and Betsy Whyte, who became internationally renowned. Recording the songs for Edinburgh’s School of Scottish Studies, which he co-founded, Henderson reported that it “was like holding a bucket under Niagra Falls”.’

The ballad tradition would inspire the 1950s and 60s folk music revivals, through singers such as Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Jean Redpath and The Watersons. It continues to inspire traditional musicians in the present day, in the songs and music of such as the Battlefield Band, Karine Polwart, and Old Blind Dogs.

Versions of ‘Tam Lin’ have been recorded by many folk artists including Fairport Convention, Pentangle, and Steeleye Span. ‘The Ballad of Tam Lin’ or ‘The Devil’s Widow’, a contemporary re-telling of the ancient Scottish ballad, is a 1970 horror film directed by Roddy McDowall and starring Ava Gardner and Ian McShane.

- Author:

- Publication Date:

- 1800

- Imprentit:

‘Kempion’

‘Come here come here you freely feed

And lay your head on my knee

The hardest weird I will you read

That e’er was read to a lady

O meikle dollour sall you dree

An ay the sat seas or ye swim

An fair mair dolour sall ye dree

Or east-muir crags or ye them clim’Frae ‘Kempion’