A! fredome is ane nobill thing,

Fredome mais man to haf liking;

Fredome all solas to man gifis:

He lifis at es that frely lifis!

The abuin represents aiblins the best-kent lines o the byordinar 13,000-line lang, 14th-century epic poem, The Brus: the earliest ayebidin wark o Scots literature, whase pooerfu and universal message o freedom has echoed doon through the centuries. The maist mensefu exemplar o early Middle Scots that we hae, it was scrievit in the 1370s by Aiberdeen kirkman and courtier John Barbour. The verse romance gies a virrsome and semi-historic accoont o the exploits o King Robert I (d. 1329) – better kent the day as ‘Robert the Bruce’ – and his richt-haun chiel, ‘the Guid’ Sir James Douglas, durin the Scottish wars o independence o the early 1300s. In Barbour’s ain wirds:

King Robert off Scotland

That hardy wes off hart and hand,

And gud Schir James off Douglas

That in his tyme sa worthy was […]

Off thaim I think this buk to ma.

It sterts aff wi the untimeous deith o Alexander III in 1286 and ends wi the deith o Douglas in Spain in 1330 – while takkin Bruce’s hert on a posthumous crusade – and the burial o ‘the Kyngis hert at the abbay’ o Melrose. It’s nae muckle surprise, hooivver, that the jewel in the croon o the poem is a michty description o the 1314 Battle o Bannockburn, whan, in a Dauvit-agin-Goliath birl o history, an oot-nummert Scots airmy heidit up by Bruce sent hame a faur mair muckle English host tae think again. Barbour’s gleg and forritsome verse fair breeshles ye alang wi the tale and gars ye feel as though ye’ve flittit richt back intae the 14th century.

Although there’s nae doot that Robert I was gey mair complex and trauchlesome nor the epic lets on, Barbour maks yaise o poetic and patriotic licence tae portray Bruce as baith a kenspeckle model o chivalric kingship and as the richtfu king o a free-staunin Scotland – bowsterin the image that Robert I warked gey hard tae projeck durin his ain reign. This maks muckle sense gin we tak tent o the fact that the composition o The Brus was maist likely owerseen by Robert II, whae ruled fae 1371 until 1390. The grandbairn o Robert the Bruce and the first monarch o the Stewart dynasty, he would hae been gey keen tae associate hissel wi the Bruce legacy – seekin tae strengthen his staunin through forderin his status as the leal heir o the legendary fechter-king.

At the ae time, hooivver, the kenably skyrie and muckle presence o Sir James Douglas oot-through the nairrative, alang wi the dominance o his descendants – the weel-forrit Douglas lairds – at the royal coort, micht weel mynt at the patronage o his heirs insteid; or, at the verra least, taewart ane o Barbour’s main sources haein been a noo tint life o the ‘gud Schir James off Douglas’. Academic debate anent Barbour’s sources fur The Brus aye hauds forrit and is fykie; in summary, hooivver, Barbour is likely tae hae brocht thegither and biggit on a wheen oral and scrievit sources anent baith Bruce and Douglas.

Lear mair aboot The Brus by John Barbour (c 1320-1395)

Aft cried the ‘faither o Scots poetry’, John Barbour was likely born sometime atween 1320 and 1330; in onie event, weel within the generation immediately follaen the Battle o Bannockburn that he would later immortalise in sic byordinar verse. Scotland as a kinrick was bein wrocht aboot him, wi the noo faur-kent ‘Declaration o Arbroath’ scrievit and sent furth tae the Pope in 1320, sax year efter Bannockburn, fur tae fend Scotland’s freedom fae thirldom forby uphaud the kingship o Robert the Bruce. Barbour’s lugs as a wee laddie will syne hae been fou o tales o the michty battle fae fowk whae seen it wi their ain een and focht it wi their ain swords. He nae doot had some mindin, tae, on hoo the kintra felt whan King Robert I deed in 1329.

We dinnae ken muckle anent his early life, but, by 1357, Barbour was Airchdeacon o St Machar’s Cathedral in Aiberdeen, and he would gang on tae haud a wheen posts in the royal court forby. We also ken that he spent time in England and in France fur tae unntertak study (Scotland’s first university, St Andraes, wouldnae be estaiblished until 1413). Although ither historical warks hae been attributit tae Barbour alang wi ‘The Brus‘, we are siccar anely anent his authorship o the epic forby a noo tint genealogical history o the Stewart royal hoose (‘The Stewartis Oryginalle’). He deed in 1395.

In monie weys, ‘The Brus’ can be seen as haudin forrit wi the Brucean propaganda – and demonisation o England tae Scotland’s fordel – seen at its heicht in the Declaration o Arbroath. There are kenable parallels, fur exemple, atween the Declaration o 1320 and Barbour’s interpretation, scrievin in the 1370s, o Bruce’s address tae his men afore the battle. Fur tae justify the Scots gaun tae war agin the English, Barbour has Bruce invoke

‘the mekill ill/That thai and tharis has done us till’ – this ‘mekill ill’ siccarly the ae ‘trauchles and dree brocht by the English […] the deeds o ill-daein, slauchter, strouth, reivin, and arson, the imprisonin o prelates, the burnin doun o monasteries, the choreyin, and the pittin tae deid o monks and nuns – forby monie ither coontless ootrages that he perpetratit agin oor people, wi nae regaird fur age or sex, religion or rank […]’ set oot in the Declaration.

Forby Barbour has Bruce contrast the morally unassailable motives and divinely uphaudit cause o the Scots wi the morally-tuim, unhaly, pridefu and gutsy ambitions o the English: whaur the latter shaw ‘mekill pryd’ and fecht ‘for thair mycht anerly‘, the Scots ‘haf the rycht/And for the rycht ay God will fecht‘, and dae or dee ‘for our lyvis/And for our childer and our wyvis/And for the fredome of our land‘. Aince mair, we cannae but be mindit on the best-kent lines o the Declaration, ‘It is, forsuith, no fur glory nor siller nor honours that we fecht, but fur freedom alane […]‘.

The nairrative o Scottish nationhood centred aroond wyteless victimhood, haly exceptionalism and moral maistery relative tae its mair muckle neebour o England maun aye hae resonatit wi Scots in the 1370s, and Barbour pleys on thon tae the fou in ‘The Brus’.

The leid-kist o the Middle Scots o ‘The Brus’ is replete wi wirds that we aye ken in Modern Scots the day, awbeit whiles in aulder forms o spellin: fae ‘hame’, ‘heid’ and ‘kirk’, tae ‘dochtir’, ‘eftir’, ‘kinrick’, ‘grete’, ‘fecht’, ‘maist’, ‘mycht’, ‘rycht’ ‘deid’, ‘mekill’, ‘skaith’, ‘wrang’ ‘gyf’, ‘thyrldome’ ‘blyth’ ‘gar/gart’ and ‘sekyrly’.

The epic is stappit fou o kenspeckle Middle Scots grammatical merkers sic as the past tense ‘-it/-yt’ endin on weak verbs that we aye see and hear in monie modern Scots verbs. Fur exemple, verbs sic as defendit, governyt, schawyt, callit, askit, cryit, hangyt, assayit, commaundyt, makyt, assemblyt, concordit, recordit, assentit, arestyt, degradit, fulfillyt and preservyt are tae be seen in nearhaun ivery verse. Forby there are present participles in ‘-and'(sic as plesand, apperand, takand, ridand, lauchand, and cumand) and the kenable Middle Scots’-is’ inflection tae merk possessives and plurals. Fur exemple, Barbour refers tae “the kingis hert’ and has Bruce tell his men tae be ready fur the fechtin ‘in bataillis with baneris displayit‘; or, descrievin Douglas, Barbour scrieves that ‘he wes in all his dedis lele” and ’till gud Ector of Troy mycht he / In mony thingis liknyt be’.

Mairower, the fricative ‘-ch’ soond, aye present in Modern Scots, is seen scrievit in monie wirds (sic as thocht, mycht, rycht, brocht) and we see Middle Scots pronouns includin the Norse-derived forms ‘thai/thaim’ (compare wi Auld Icelandic ‘þeir, þheim’). Finally, the epic contains coontless instances o the gey kenable Middle Scots ‘quh-‘ at the stert o wirds that noo stert wi ‘wh-‘; as in quhat, quhar, quhethir, quhen, quha. Fur exemple, at the verra stert o the epic, settin the scene fur the events tae follae, Barbour scrieves,‘Quhen Alexander the King was deid/That Scotland haid to steyr and leid’; or, later, referrin tae the Douglas, ‘Bot quha in battail mycht him se […]’.

‘The Brus’ could threap renoon no lang efter its scrievin; it was clearly weel-kent and respectit by the twa maist mensefu 15th-century chroniclers o Scottish history, Andrew o Wyntoun and Walter Bower, baith o whom (awbeit tae sindry degrees) quote fae and refer their readers tae ‘the Bruss buke’. As weel as shawin the influence o Barbour’s nairrative on the tellin o Scotland’s history, sic references speik forby tae the familiarity o the readership o Wynton and Bower wi the epic and whit maun hae been the relatively widespread availability o manuscripts o ‘The Brus‘ durin thon era.

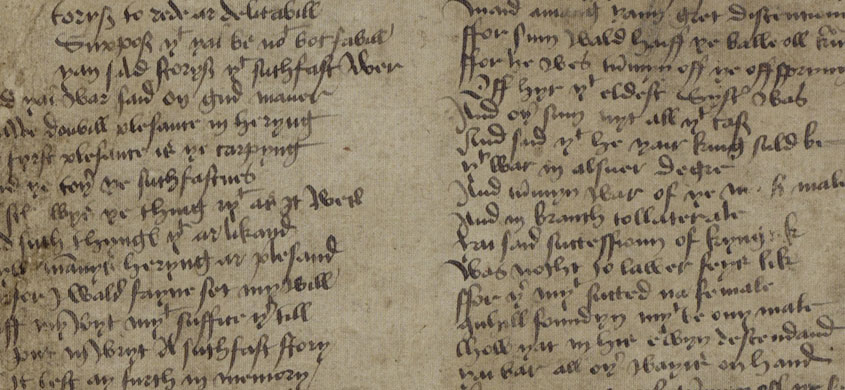

Although ‘The Brus’ was first set doon in the 14th century, we ken it the day anely fae twa manuscripts fae the later 15th century (the Cambridge ane o 1487 and the Embra ane o 1489), baith transcribit by the ae scribe. Testament tae its ayebidin popularity, we hae muckle evidence o its bein prentit oot-through the 16th and 17th centuries, includin by kenspeckle prenters sic as Robert Lekprevik (the maist important prenter o the 1570s); Embra prenter Andro Hart (1616/1620); Gedeon Lithgow, prenter tae the University o Embra (1648), and Robert Sanders, prenter tae the city and university o Glesga (1672). Lowpin forrit tae the 19th century, nae less nor Sir Walter Scott, ane o the maist weel-kent scrievers in Scotland’s history, taen muckle inspiration fae Barbour’s ‘Brus’ – includin in his gey popular ‘Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories taken from Scottish History’ (1828) and the final ane o his Waverley novels, ‘Castle Dangerous’ (1831). The maist accessible modern edition o the text – wi foreanent prose owersettin intae English – is thon o A.A.M Duncan, first furthset in 1997.

A! fredome is ane nobill thing,

Fredome mais man to haf liking;

Fredome all solas to man gifis:

He lifis at es that frely lifis!

The above represents perhaps the best-known lines of the magnificent 13,000 line-long, 14th-century epic poem, The Brus: the earliest surviving work of Scots literature, whose powerful and universal message of freedom has echoed down through the centuries. The most significant example of early Middle Scots that we have, it was written in the 1370s by Aberdeen ecclesiast and courtier John Barbour. The verse romance gives a lively and semi-historic account of the exploits of King Robert I (d. 1329) – better known today as ‘Robert the Bruce’ – and his right-hand man, ‘the Good’ Sir James Douglas, during the Scottish wars of independence of the 1300s. In Barbour’s own words:

King Robert off Scotland

That hardy wes off hart and hand,

And gud Schir James off Douglas

That in his tyme sa worthy was […]

Off thaim I think this buk to ma.

It begins with the untimeous death of Alexander III in 1286 and ends with the death of Sir James Douglas in Spain in 1330 – while taking Bruce’s heart on a posthumous crusade – and the burial of ‘the Kyngis hert at the abbay’ of Melrose. It is no great surprise, however, that the jewel in the crown of the poem is a mighty description of the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn, when, in a David-against-Goliath turn of events, an out-numbered Scots army headed up by Bruce sent home a far bigger English army to think again. Barbour’s punchy and fast-paced verse really sweeps you up in the tale and transports you right back to the 14th century.

Although there’s no doubt that Robert I was far more complex and problematic than the epic suggests, Barbour makes use of poetic and patriotic licence to portray Bruce as both an exemplary model of chivalric kingship and as the rightful king of an independent Scotland, underlining the image that Robert I worked extremely hard to project during his own reign. This makes a lot of sense if we consider the fact that the composition of The Brus was most likely overseen by Robert II, who ruled from 1371 until 1390. The grandson of Robert the Bruce and the first monarch of the Stewart dynasty, he would have been very keen to associate himself with the Bruce legacy – seeking to strengthen his standing through promoting his status as the loyal heir of the legendary warrior-king.

At the same time, however, the remarkably significant and favourable presence of Douglas throughout the narrative, along with the dominance of his descendants – the prominent Douglas lords – at the royal court, might well point towards the patronage of his heirs instead; or, at the very least, towards one of Barbour’s main sources having been a now lost life of the ‘gud Schir James off Douglas’. Fastidious academic debate about Barbour’s sources continues to this day; in summary, however, it is likely that Barbour brought together and drew upon a range of oral and written sources about both Bruce and Douglas.

Learn more about The Brus by John Barbour (c 1320-1395)

Often called the ‘father of Scots poetry’, John Barbour is likely to have been born sometime between 1320 and 1330; in any event, well within the generation immediately following the Battle of Bannockburn that he would later immortalise in such brilliant verse. Scotland as a kingdom was being forged around him, with the now famous ‘Declaration of Arbroath’ composed and sent to the Pope in 1320, six years after Bannockburn, in order to defend Scotland’s freedom from servitude and uphold the kingship of Robert the Bruce. As a wee boy, Barbour’s ears will have been full of tales of the mighty battle from people who saw it with their own eyes and fought it with their own swords. He may well also have remembered how the country felt when King Robert I died in 1329.

We don’t know much about his early life, but, by 1357, Barbour was Archdeacon of St Machar’s Cathedral in Aberdeen, and he would go on to hold a number of posts in the royal court as well. We also know that he spent time in England and in France in order to undertake study (Scotland’s first university, St Andrews, wouldn’t be established until 1413). Although other historical works have been attributed to Barbour along with ‘The Brus‘, we are certain only about his authorship of the epic and a now lost genealogical history of the Stewart royal house (‘The Stewartis Oryginalle’). He died in 1395.

In many ways, ‘The Brus’ can be seen as continuing the Brucean propaganda – and demonisation of England to Scotland’s advantage – seen at its height in the Declaration of Arbroath. There are notable parallels, for example, between the Declaration of 1320 and Barbour’s interpretation, writing in the 1370s, of Bruce’s address to his men before the battle. To justify the Scots going to war against the English, Barbour has Bruce invoke

‘the mekill ill/That thai and tharis has done us till’ – this ‘mekill ill’ surely the same ‘trauchles and dree brocht by the English […] the deeds o ill-daein, slauchter, strouth, reivin, and arson, the imprisonin o prelates, the burnin doun o monasteries, the choreyin, and the pittin tae deid o monks and nuns – forby monie ither coontless ootrages that he perpetratit agin oor people, wi nae regaird fur age or sex, religion or rank […]‘ set out in the Declaration.

Moreover, Barbour has Bruce contrast the morally unassailable motives and divinely ordained cause of the Scots with the morally lacking and unholy ambitions, the pride and avarice, of the English: where the latter show ‘mekill pryd’ and fight ‘for thair mycht anerly’, the Scots ‘haf the rycht/And for the rycht ay God will fecht’, and take to the battlefield ‘for our lyvis/And for our childer and our wyvis/And for the fredome of our land’. Once again, we cannot but be reminded of the best-known lines of the Declaration, ‘It is, forsuith, no fur glory nor siller nor honours that we fecht, but fur freedom alane […]’.

The narrative of Scottish nationhood centred around blameless victimhood, holy exceptionalism and moral superiority relative to its bigger southern neighbour of England must still have resonated with Scots in the 1370s, and Barbour plays on this to the full in ‘The Brus‘.

The vocabulary of the Middle Scots of ‘The Brus‘ is replete with words that we still recognise in Modern Scots today, albeit sometimes in older forms of spelling: from ‘hame’, ‘heid’ and ‘kirk’, to ‘dochtir’, ‘eftir’, ‘kinrick’, ‘grete’, ‘fecht’, ‘maist’, ‘mycht’, ‘rycht’ ‘deid’, ‘mekill’, ‘skaith’, ‘wrang’ ‘gyf’, ‘thyrldome’ ‘blyth’ ‘gar/gart’ and ‘sekyrly’.

The epic is full of unambiguous Middle Scots grammatical markers such as the past tense ‘-it/-yt’ ending on weak verbs that we still see and hear in many modern Scots verbs. For example, verbs such as defendit, governyt, schawyt, callit, askit, cryit, hangyt, assayit, commaundyt, makyt, assemblyt, concordit, recordit, assentit, arestyt, degradit, fulfillyt and preservyt are to be seen in every other verse. In addition, there are present participles in ‘-and’ (such as plesand, apperand, takand, ridand, lauchand, and cumand) and the immediately recognisable Middle Scots ‘-is’ inflection to mark possessives and plurals. For example, Barbour refers to ‘the kingis hert’ and has Bruce tell his men to be ready for the fighting ‘in bataillis with baneris displayit‘; or, describing Douglas, Barbour writes that ‘he wes in all his dedis lele’ and ’till gud Ector of Troy mycht he / In mony thingis liknyt be’.

Moreover, the fricative ‘-ch’ sound, still present in Modern Scots, is seen written in many words (such as thocht, mycht, rycht, brocht) and we see Middle Scots pronouns including the Norse-derived forms ‘thai/thaim’ (compare with Old Icelandic ‘þeir, þheim’). Finally, the epic contains countless instances of the visually striking Middle Scots ‘quh-‘ at the start of words that now start with ‘wh-‘; as in quhat, quhar, quhethir, quhen, quha. For example, at the very start of the epic, setting the scene for the events to follow, Barbour writes,’Quhen Alexander the King was deid/That Scotland haid to steyr and leid’; or, later, referring to the Douglas, ‘Bot quha in battail mycht him se […]’.

‘The Brus’ could claim renown not long after its writing; it was clearly well-known and respected by the two most significant 15th-century chroniclers of Scottish history, Andrew of Wyntoun and Walter Bower, both of whom (albeit to differing degrees) quote from and refer their readers to ‘the Bruss buke.’ As well as demonstrating the influence of Barbour’s narrative on the telling of Scotland’s history, such references also speak to the familiarity of the readership of Wynton and Bower with the epic and what must have been the relatively widespread availability of manuscripts of ‘The Brus’ during that era.

Although ‘The Brus’ was first set down in the 14th century, we know it today only from two manuscripts from the later 15th century (the Cambridge one of 1487 and the Edinburgh one of 1489), both transcribed by the same scribe. Testament to its enduring popularity, we have significant evidence of its being printed throughout the 16th and 17th century, including by famous printers such as Robert Lekprevik (the most important printer of the 1570s); Edinburgh printer Andro Hart (1616/1620); Gedeon Lithgow, printer to the University of Edinburgh (1648), and Robert Sanders, printer to the city and university of Glasgow (1672). Springing forward to the 19th century, no less than Sir Walter Scott, one of the best-known writers in Scotland’s history, drew much inspiration from Barbour’s Brus – including in his highly popular ‘Tales of a Grandfather; Being Stories taken from Scottish History’ (1828) and the last of his Waverley novels, ‘Castle Dangerous’ (1831). The most accessible modern edition of the text – with facing-page prose translation into English – is that of A.A.M Duncan, first published in 1997.

- Author:

- John Barbour

- Publication Date:

- 1489

- Imprentit:

Aberdeen

The Brus

A! Freedom is a noble thing,

Freedom maks man blythe

Freedom aw solace tae man gies

He lives at ease that freely livesA! fredome is ane nobill thing,

Fredome mais man to haf liking;

Fredome all solas to man gifis:

He lifis at es that frely lifis!