Peter Hately Waddell wis born in Balquhatston, Stirlingshire, in 1817 but grew up an wis educatit at scuil an university in Glesga. Waddell trainit as a minister an sidit wi the seceeders whae formit the Free Kirk o Scotland at the Muckle Disruption o 1843. Efter servin as minister fur a wee while at Rhynie in Aiberdeenshire an syne at Girvan, Waddell left the Free Kirk (he wis unwillin tae accept the Westminster Confession in fou, especially on the question o voluntaryism an the duties o baillies). He foondit his ain free-staunin kirk at Girvan, cried ‘the Kirk o the Future’ (also kent as ‘Waddell’s Kirk), takkin a muckle pairt o the kirk-fowk wi him. Nearhaun twa decade later, in 1862 he flittit tae Glesga an stertit tae preach in the City Hall as a free-staunin minister, whaur his unco virr as a preacher brocht him a muckle kirk-fowk. In 1888, he rejyned the Estaiblished Kirk o Scotland afore retirin due tae auld age in 1890. He deed the follaen year.

Waddell wis a chiel o wide-rangin interests an wis a prolific scriever as weel as a pooerfu orator on mony sindry subjecks, fae religion an history tae geography an linguistics. Amang mony ither things, he gied a series o lectures anent Renan’s ‘Life o Jesus’, scrievit a muckle historical wark entitled ‘Ossian an the Clyde’ that threapit the authenticity o Macpherson’s Ossianic poems Macpherson; contributit an unco series o letters anent Ptolemy’s map o Egypt tae a Glesga journal; an, reflectin his profoond admiration fur Burns, issued a new edition o his poems, which includit extensive criticism o earlier versions.

His maist mensefu contribution tae literature, hooivver, wis aiblins his 1871 owersettin ‘The Psalms: frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ follaed in 1879 by an owersettin o Isaiah; makkin Waddell the first chiel tae owerset the bible intae Scots fae the original leid (in this case, Hebrew) as opposed tae an existin English version.

Lear mair aboot The Psalms frae Hebrew intil Scottis

The lack o a Scots Bible durin the Reformation is weel kent as a muckle factor in the douncome o Scots as a prestige an institutional leid, wi reformers turnin insteid tae English leid bibles. The Geneva Bible wis dominant in Scotland until weel intae the 17th century, afore bein owertaen in popularity by the Authorized Version (AV).

This shouldnae owershadow, hooivver, the mony Scots bible owersettins that hae been producit ower the centuries. Though there his ne’er been an owersettin o the complete text, there exists a gey rich body o biblical Scots, fae 14th century fragments tae Nisbet’s early 16th century owersettin o the New Testament, an fae Waddell’s 1871 ‘The Psalms: Frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ tae Lorimer’s byous 1983 owersettin o the New Testament fae the original Greek.

On the hale, Scots bible owersettins faa intae twa main groups. On the ae haun, we hae the religiously motivatit owersettins o the 16th century, a Scottish expression o the wider Reformation commitment tae vernacular versions o the bible. On the ither haun, efter a gap o near-haun three century, the steady stream o owersettins that we see fae the mid-19th century onwart are mair linguistically nor religiously motivatit. Unnertaen at a time whan Scots had tholed centuries o attritition, these owersettins can be seen as pairt ettlin at romantic revival, pairt lamentation fur the dowie status o the leid.

Waddell’s ‘The Psalms: Frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ clearly forms pairt o the broad latter group an it is tae the details o his text that we noo turn.

Waddell wis a muckle admirer o Burns, whae had, in his opinion, heezed Scots up as a leid o poetry an ‘rescued [it] fae obliteration.’ Syne it aiblins shouldnae conflummix that Waddel chuisit twa o the maist poetic buiks o the Bible (the Psalms an later Isaiah) tae owerset intae Scots.

His ain kennin o Scots wis rich. As weel as the spoken Scots that he grew up wi, he would hae been surroondit by Scots in the communities he servit as a minister. Forby he could draw on muckle scholarly an linguistic insicht.

Waddell is kenspeckle fur bein the first chiel tae unnertak an owersettin intae Scots fae the original leid o the bible as opposed tae an existin English version (Lorimer would follae in his fit-steps in the 20th century wi his owersettin o the New Testament fae the original Greek).

This maks Waddell’s Scots owersettin o the bible kenably mair distinct an free-staunin nor earlier owersettins based on an English text, which retained muckle by wey o English vocabularly an grammar.

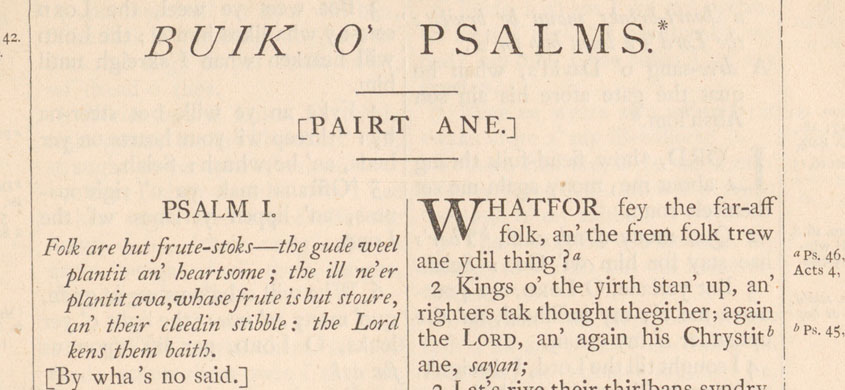

In his owersettin o the Psalms, Waddell frequently hauds wide o wirds o Latin origin, insteid creatin a wheen o Germanic-soondin compoonds, which Waddell threapit gied a closer sense o the original Hebrew meanin. At the ae time, we can jalouse that this was pairtly doon tae a desire on Waddell’s behauf tae mak the Scots as sindry fae the English o the AV as possible. Forby Waddell gied muckle significance tae the Germanic roots o Scots. In his lecture, ‘Genius an Morality o Robert Burns’, Waddell threapit that Scots ‘adheres mair perfectly in its root tae the auld Teutonic nor the English’ an celebrates hou ‘genuine Scotch’ wirds are ‘aamaist pure German’.

Fur exemple, whaur the AV his generation, integrity an testimony, Waddell his kithgettin, leal-gate an truth-tryst. Forby Waddell’s yaise o richt-recht fur to judge is sib tae the German richten, as is his righters, fur judges, sib tae the German Richter.

Syne the Scots in Waddell’s Psalms is kenably an consciously gey Germanic, tae the extent o scrievin the Romance inheritance o Scots oot o history.

Waddell employs a haunfu o Scots archaisms, fur exemple, yo an scho fur you an she, fuhre meanin to go, redd meanin deliver, an thring meanin oppress. Forby there is the Middle Scots wird ‘Scottis’ in the title o the owersettin. It is thocht that Waddell yaised this wird fur tae unnerline the status o Scots as a free-staunin leid, ‘nae a mere dialect, but a tongue cognate wi the English…nae a dialect o the English, but a dialect o the Teutonic, e’en as English itsel is’, as he scrievit in his aforementioned lecture on Burns. The alternative terms, on the ither haun, were baith scunnersome: Scotch wis an English term, whilst Scots in the 19th had nae muckle prestige.

The oweraa effect is o a rich an free-staunin Scots, wi elements o archaism an literary artefact mellin wi the braw virr o authentic Scots as it would hae been spoken in Waddell’s era. Waddell’s Dauvit, whae speaks wi the voice o the common fowk, is a strang example o the latter.

At a time whan scrievit Scots wis restrictit maistly tae informal dialogue in novels (sic as thaim o Walter Scott) or tae poetry (sic as thon o Burns), Waddell’s owersettin o the Psalms is forby kenspeckle fur creatin a formal prose register o Scots, appropriate tae owersettin the bible, fur which there wis nae mensefu precedent (Nisbet’s 16th century owersettin o the New Testament wisnae setten furth until the 20th century, an it seems gey unlikely that Waddell would hae had access tae Riddell’s mid-nineteenth century owersettin o the Psalms intae Scots). Burns wis, o coorse, an important resource, hooivver, its informality meant that it couldnae be yaised as a straight-forrit prose model fur a bible owersettin. As Waddell scrievit hisel in his ‘Notice Tae The General Reader’ prentit alangside the Psalms, ‘a gey muckle nummer o terms employit by Burns are employed here tae […] but the expressions or phraseology maist frequently employed by Burns couldnae, fur gey kenspeckle reasons, be latten intae an owersettin o the Bible’.

Waddell kent that he wis yaisin Scots in an unco wey fur the era. In his ‘Notice’, he laments hou the ‘true vernacular […] o the kintra’, spoken fae the days o the Reformation an the Covenant, an wi which the Owersetter wis familiar in his barnheid, ‘micht seem unco tae the young o the present generation’. He gangs on tae threap, hooivver, that ‘ony unconess […] maun result solely fae the newness o its grammatical application tae sae solemn a theme as the Wird o God.’ Here we see clearly hou Waddell is eident tae revive an heeze up the Scots leid by demonstration hou it is maist capable o, an suitable fur, expressin the Wird o God.

Waddell’s byous owersettin o the Psalms thaimsels is complimentit by the rich an formal Scots o the lengthy innin – a gey rare exemple o extendit formal prose durin that era – as weel as aa the paraphernalia that his readers would hae been yaised tae in English versions o the bible: fae marginal notes an fitnotes tae explanations o the terms yaised in the original Hebrew headins. Forby it’s couthie tae note that Waddell yaises marginal notes tae pynt oot some o his favourite pairts. At the stert o Psalm VIII, fur exemple, he scrieves, ‘tak tent as ye read: thar’e no mony grander kirk sangs nor this’.

Testament tae Waddell’s linguistic prowess, his owersettin fae the original Hebrew intae Scots wis gey accurate an handfast. In keepin wi traditional pratick, he yaises italics fur wirds nae in the original but eikit tae mak the meanin mair clear. Forby, on a wheen o occasions, Waddell disagrees wi the owersettin o the AV. In twa o these cases, the Revised Version agrees wi Waddell’s owersettin. In twa mair, the RV retains the owersettin o the AV but gies alternative readins, sib tae Waddell’s, in the margin.

In aa o the abuin, Waddell’s ‘The Psalms: frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ bears the gree in creatin a rich an free-staunin register o Scots suitable fur the owersettin o the bible. Forby it bears the gree in heezin up the leid, makkin clear that Scots could be yaised fur aa purposes, no jist informal anes. The text wis myntit fur public usage an gaed through several editions.

Peter Hately Waddell was born in Balquhatston, Stirlingshire, in 1817 but grew up and was educated at school and university in Glasgow. Waddell trained as a minister and sided with the seceders who formed the Free Church of Scotland at the Great Disruption of 1843. After serving as minister for a short time at Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, and then at Girvan, Waddell left the Free Church (he was unwilling to accept the Westminster Confession in full, especially on the question of voluntaryism and the duties of magistrates). He founded his own independent church at Girvan, called the ‘Church of the Future’ (also known as Waddell’s Church), taking a substantial part of his congregation with him. Nearly two decades later, in 1862, he moved to Glasgow and began to preach in the City Hall as an independent minister, where his oratorical vigour drew a large congregation. In 1888, he rejoined the Established Church of Scotland before retiring due to old age in 1890. He died the following year.

Waddell was a man of wide-ranging interests and was both a prolific writer and a powerful orator on many different subjects, from religion and history to geography and linguistics. Amongst many other things, he gave a series of lectures on Renan’s ‘Life of Jesus’, wrote a major historical treatise entitled ‘Ossian and the Clyde’ that argued in favour of the authenticity of Macpherson’s Ossianic poems; contributed a remarkable series of letters on Ptolemy’s map of Egypt to a Glasgow journal; and, reflecting his profound admiration of Burns, issued a new edition of his poems, which included extensive criticism of earlier versions.

Perhaps his most significant contribution to literature, however, was his 1871 ‘The Psalms: frae Hebrew intil Scottis’, followed in 1879 by a translation of Isaiah, making Waddell the first person ever to translate the bible into Scots from the original language as opposed to an existing English version.

Learn more about The Psalms frae Hebrew intil Scottis

The lack of a Scots bible during the Reformation is well-recognised as a major factor in the demise of Scots as a prestige and institutional language, with reformers turning instead to English language bibles. The Geneva bible was dominant in Scotland until well into the 17th century, before being overtaken in popularity by the Authorized Version (AV).

This shouldn’t, however, overshadow the many Scots bible translations that have been produced over the centuries. Though there has never been a translation of the complete text, there exists a remarkably rich body of biblical Scots, from 14th century fragments to Nisbet’s early 16th century translation of the New Testament, and from Waddell’s 1871 ‘The Psalms: Frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ to Lorimer’s magnificent 1983 translation of the New Testament from the original Greek.

On the whole, Scots bible translations fall into two main groups. On the one hand, we have the religiously motivated translations of the 16th century, a Scottish expression of the wider Reformation commitment to vernacular versions of the bible. On the other hand, after a gap of nearly three centuries, the steady stream of translations that we see from the mid-19th century onwards are more linguistically than religiously motivated. Produced at a time when Scots had suffered from centuries of attrition, these translations can be seen as part attempt at romantic revival, part lamentation for the dire status of the language.

Waddell’s ‘The Psalms: Frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ clearly forms part of this broad latter group, and it is to the details of his text that we now turn.

Waddell was a great admirer of Burns, who had, in his opinion, elevated Scots as a language of poetry and ‘rescued [it] from obliteration’. Given this, it should perhaps be of little surprise that Waddell selected two of the most poetic books of the bible (the Psalms and later Isaiah) to translate into Scots.

His own knowledge of Scots was rich. In addition to the spoken Scots that he grew up with, he would have been surrounded by Scots in the communities he served as a minister, and could also draw on his significant scholarly and linguistic insight.

Waddell is notable for being the first person to undertake a translation into Scots from the original language of the bible as opposed to an existing English version (Lorimer would follow in his foot-steps in the 20th century with his translation of the New Testament into Scots from the original Greek.)

This serves to make the Scots in Waddell’s translations markedly more distinct and independent than earlier translations based on an English text, which retained much by way of English vocabularly and grammar.

In his translation of the Pslams, Waddell frequently eschews words of Latin origin, instead creating numerous Germanic-sounding compounds, which Waddell argued gave a closer sense of the original Hebrew meaning. At the same time, we can assume that this was at least partly down to a desire on Waddell’s behalf to make the Scots as distinct from the English of the AV as possible.

In addition, Waddell attached great significance to the Germanic roots of Scots. In his lecture, ‘Genius and Morality of Robert Burns’, Waddell contended that Scots ‘adheres more perfectly in its root to the old Teutonic than the English’ and celebrated how ‘genuine Scotch’ words were ‘almost pure German’.

For example, where the AV has generation, integrity, and testimony, Waddell has kithgettin, leal-gate, and truth-tryst. In addition, Waddell’s use of richt-recht for to judge echoes the German richten, as does his righters, for judges, echo the German Richter. So the Scots in Waddell’s Psalms is markedly and consciously Germanic, to the extent of writing the Romance inheritance of Scots out of history.

Waddell employs a handful of Scots archaisms, for example, yo and scho for you and she, fuhre meaning to go, redd meaning deliver, and thring meaning oppress. There is also the Middle Scots word Scottis in the title of the translation. It is thought that Waddell used this word in order to underline the status of Scots as independent language, ‘not a mere dialect, but a tongue congate with the English…not a dialect of English, but a dialect of the Teutonic, even as English itself is’, as he put it in his aforementioned lecture on Burns. The alternative terms, on the other hand, were both problematic: Scotch was an English term whilst Scots in the 19th century lacked any prestige.

The overall effect is of a rich and independent Scots, with elements of archaism and literary artefact blending with the vigour of authentic Scots as it would have been spoken in Waddell’s time. Waddell’s David, who speaks with the voice of the common people, is a strong example of the latter.

At a time when written Scots was largely restricted to dialogue in novels (such as those of Walter Scott) or to poetry (such as that of Burns), Waddell’s translation of the Psalms boldly created a formal prose register of Scots, appropriate to translating the bible, for which there was no meaningful precedent (Nisbet’s 16th century translation of the New Testament was not published until the 20th century and it seems unlikely that Waddell would have had access to Riddell’s mid-nineteenth century translation of the Psalms into Scots). Burns was, of course, an important resource, however, the informality of the Scots meant that it was unsuitable as a straightforward model for biblical prose. As Waddell wrote himself in his ‘Notice To The General Reader’ printed alongside the Pslams, ‘a very large number of terms employed by Burns are also employed here […] but the expressions or phrases most frequently employed by Burns could not, for obvious reasons, be admitted into a translation of the Bible.’

Waddell was conscious of the fact that he was using Scots in a novel and unfamilar way for the era. In his ‘Notice’, he laments how the ‘true vernacular […] of the country’, spoken from the days of the Reformation and the Convenant, and with which the translator was familiar in his childhood, ‘may seem strange to the young of the present generation.’ He goes on to argue, however, that ‘any strangeness […] must result solely from the newness of its grammatical application to so solemn a theme as the Word of God.’

Here we see clearly how Waddell is keen to revive and to elevate the Scots language by demonstrating how it is fully capable of, and suitable for, expressing the Word of God.

Waddell’s impressive translation of the Psalms themselves is complimented by the rich and formal Scots of the lengthy introduction – a rare example of extended formal prose in Scots – as well as all of the paraphernalia that his readers would have been used to in English versions of the bible: from marginal notes and footnotes to explanations of the terms used in the original Hebrew headings. It’s also touching to note that Waddell uses the marginal notes to point out some of his favourite parts. At the beginning of Psalm VIII, for example, he writes: ‘tak tent as ye read: thar’e no mony grander kirk sangs nor this’ (pay attention as you read: there aren’t many grander psalms than this).

Testament to Waddell’s linguistic prowess, his translation from the original Hebrew into Scots wis extremely accurate and meticulous. In keeping with traditional practice, he uses italics to indicate where words not in the original have been added to make the meaning clearer. Moreover, on a number of occasions, Waddell disagrees with the AV. In two of these cases, the Revised Version (RV) agrees with Waddell’s translation. In a further two, the RV retains the translation of the AV but provides alternative readings, similar to Waddell’s, in the margin.

In all of the above, Waddell The Psalms: frae Hebrew intil Scottis’ succeeds in creating a rich and independent Scots translation in a register suitable for biblical translation. In this, he also succeeds in elevating the language, making clear that Scots could be used for all purposes, not just informal ones. The text was intended for public usage and went through several editions.

- Author:

- P Hately Waddell

- Publication Date:

- 1871

- Imprentit:

Edinburgh

Psalm VIII

O Lord, Laird o’ us a’, how

lordlie’s thy name atowre a’

the yirth; wha setten haist thy

nameliheid abune the hevins.Frae bairnies’ mouthes an’

weanies fine, ye hae ettled might

again a’ yer faes; that the wrang-

doer baith an’ wha rights himsel, ye may whush them ane wi’ anither.