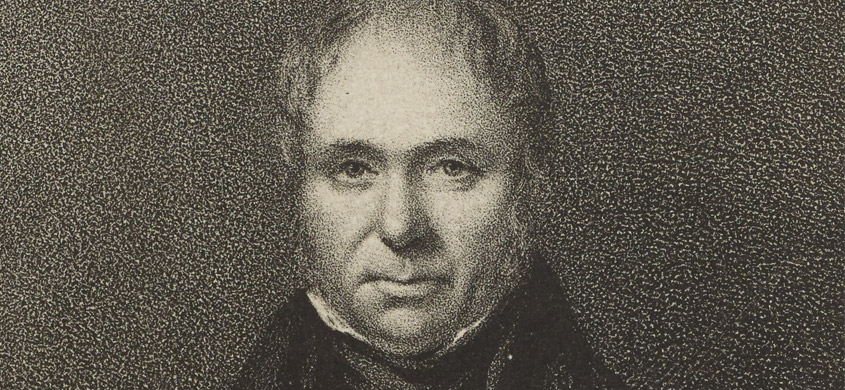

Hailin frae East Calder in Midlothian, Alexander Rodger flittit tae Glesga whaur he bade in the wabster’s districk o Brigton. He became kent in popular Radical literature fir his satirical broadsides, notably in a parody o Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Carle Now the King’s Come’. In this polemic Rodger gies a flytin tae Scott an whit he views as his toadyin tae the monarchy as the Scottish gentry celebratit King George IV’s visit tae the Scottish capital in 1822. Rodger wid alsae satirise the Regency Crisis an the Hanoverian succession in a comical re-tellin o ‘The Mucking o’ Geordie’s Byre’.

Though a political event maistly thocht tae hae been swickit bi government agents provocateurs, Rodger wis insnorlt bi the authorities in the 1820 Glesga Radical Risin an wis furder indictit in a sedition trial fir his scrievins tae a Reformist newspaper in Glesga. A popular poet an satirist, Rodger’s sangs featurt in weel-kent Scottish music collections.

Lear mair aboot Alexander Rodger (1784-1846)

Syne the early 19th century Rodger wis scrievin verse fir subversive London periodical ‘The Black Dwarf’ whiles makkin a livin baith as wabster an music teacher in Glesga.

‘The Muckin o Geordie’s Byre’ wis aready kent tae Robert Burns an is best remembert as a bothy ballad, as popularised bi 20th century Scottish entertainer Andy Stewart. Rodger’s 1819 version plots the Regency Crisis through the monarchy losin ther fairm owerseas due tae the American Revolution, tae King George III gan gyte wi the madness an doon tae the ill-daeins an dissolution o the Prince o Wales. As in Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ ower a century later, the ‘routers an grunters’ in Rodger’s polemic are schamin owerthrow an rebellion but ther designs are whummelt bi the violence o the authorities.

In ‘The Spirit of the Union: Popular politics in Scotland (The Enlightenment world)’, imprentit in 2011, author Gordon Pentland writes that lines frae Rodger’s ‘Mucking O’ Geordies Byre’ wir a common sicht on banners at Radical demonstrations.

Rodger’s satire featured in the first imprent o ‘The Spirit of the Union’, a pro-Reform newspaper unner the editorship o Gilbert MacLeod. This Radical jurnal ran tae ten nummers afore it wis broken up in Janwar 1820 whan MacLeod an Rodger wir tae be arraigned on chairges o sedition.

Rodger wis dubbed fir echt days in preeson whiles MacLeod, aready boond ower fir fower months’ incarceration, wis sentenced tae transportation fir life in Botany Bay, later commuted unner appeal tae five years. MacLeod houanivir wid die whiles servin oot his sentence in Australia.

Rodger wis sune again implicatit in alleged crimes forenenst the state, this time in the agents-provocateurs stage-managed Radical Rising in April 1820 that wid lead tae the skirmish at Bonnymuir an the executions o Andrew Hardie an John Baird at Stirling.

Rodger wis accused o bein pairty tae the scrievin o a ‘treasonable address’ – postit on the streets o Glesga on April 1 1820 an schamin the owerthrow o the British state in order tae instaw a provisional government in Scotland. Alarm spreid throu the streets as banks wir surroondit bi sodgers. Military an militia forces forgaithert on Glesga Green – reddin fir an onslaucht o Radical hordes frae sooth o the Clyde – whiles a revolutionary French airmy wis jaloused tae be encamped on Cathkin Braes.

As the revolution failed tae kythe itsel, an despite the ‘treasonable address’ bein roondly regairdit as a hoax, Rodger wid spend eleeven days in jyle whaur his defiant Radical sangs reportedly dirled oot tae sic an extent that he wis remuived tae the farthest cell at the back o the preeson. It wis here on his cell wa he wid pencil his ‘Lines Written in a Certain Bridewell by a State Prisoner’:

‘The joys o hame – my bairns, my wife;

Whilst they sit round a cheerless fire,

And wistfully at her enquire

What makes their father stay sae lang?

And if there’s ony thing gane wrang?

‘But what’s the reason I’m confined?

Nae reason, troth, can be assigned,

Unless it be, I chance to differ

Frae them wha will that I shall suffer,

And that my view o politics

Accord no wi some statesmen’s tricks.’

‘The Spirit of the Union’ case wid be the last sedition trial in Scotland afore the 1832 Reform Act. In ‘An examination of the trials for sedition which have hitherto occurred in Scotland’, in relation tae the chairges laid forenenst editor MacLeod, Lord Henry Cockburn comments: ‘The worst thing about these libels was their exaggerated animation of language. Swift, or Cobbett, or Sydney Smith, could have said most of what the prisoner said with tolerable safety, and with greater force. But vulgar reformers, who air their opinions in newspapers or at meetings, especially if they be honest and ardent, generally despise skill.’

Undauntit bi his strauchles as polemicist, in 1822 Rodger parodied Sir Walter Scott’s obsequious ode ‘Carle Now the King’s Come’, scrievit in honour o King George IV an his Royal jaunt tae Edinburgh. ‘Sawney Now the King’s Come’ wis published anonymously in the ‘London Examiner’.

‘Tell him he is great and good

And come o Scottish royal blood

To your hunkers lick his fud

Sawney now the King’s come’

It wis said that Scott yaised ilka exertion possible as he ettled tae discover the author.

Rodger continued wi his political scrievans as editor o the ‘Glasgow Reformer’. He contributit sangs an verse tae the popular collection ‘Whistlebinkie; Songs for the social circle’.

The popularity o Rodgers’ poems an sangs led tae a subscription bein raised tae prent a collection o his warks unner the guise o his humorous pseudonyms: ‘Stray Leaves from the Portfolios of Alisander the Seer, Andrew Whaup, and Humphrey Henceckle’. His wark is alsae imprentit in ‘Poems and songs, humorous, serious and satirical’.

In a parody o popular sang ‘The Reel o Bogie’, Rodger satirises the Evangelical meenisters intaigelt in the Kirk o Scotland’s 10 years conflict which wid lead tae the Disruption o 1843 an estaiblishment o the Free Kirk.

Coming from East Calder in Midlothian, Alexander Rodger moved to Glasgow where he lived in the weaving district of Bridgeton. He became recognised in popular Radical literature for his satirical broadsides, notably in a parody of Sir Walter Scott’s ‘Carle Now the King’s Come’. In this polemic Rodger gives a scolding to Scott and what he views as his toadying to the monarchy as the Scottish gentry celebrated King George IV’s visit to the Scottish capital in 1822. Rodger would also satirise the Regency Crisis and the Hanoverian succession in a comical adaptation of ‘The Mucking o’ Geordie’s Byre’.

Though a political event generally thought to have been contrived by government agents provocateurs, Rodger was ensnared by the authorities in the 1820 Glasgow Radical Rising and was further indicted in a sedition trial for his contributions to a Reformist newspaper in Glasgow. A popular poet an satirist, Rodger’s songs featured in well-known Scottish music collections.

Learn more about Alexander Rodger (1784-1846)

From the early 19th century Rodger was writing verse for the subversive London periodical ‘The Black Dwarf’ while earning a living both as weaver and music teacher in Glasgow.

‘The Muckin o Geordie’s Byre’ was already known to Robert Burns and is best remembered as a bothy ballad as popularised by 20th century Scottish entertainer Andy Stewart. Rodger’s 1819 version plots the Regency crisis from the monarchy losing their farm overseas due to the American Revolution, to King George III going crazy with madness, to the ill-doings and dissolution of the Prince of Wales. As in Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’ over a century later, the ‘routers an grunters’ in Rodger’s polemic are scheming overthrow and rebellion but their designs are thwarted by the violence of the authorities.

In ‘The Spirit of the Union: Popular politics in Scotland (The Enlightenment world)’, imprentit in 2011, author Gordon Pentland writes that lines from Rodger’s ‘Mucking O’ Geordies Byre’ were a common sight on banners at Radical demonstrations.

Rodger’s satire featured in the first number of ‘The Spirit of the Union’, a pro-Reform newspaper under the editorship of Gilbert MacLeod. This Radical organ ran to ten numbers before being broken up in January 1820 when MacLeod and Rodger were to be arraigned on charges of sedition.

Rodger was locked-up for eight days in prison while MacLeod, already bound over for four months incarceration, was sentenced to transportation for life in Botany Bay, later commuted under appeal to five years. MacLeod however would die while serving out his sentence in Australia.

Rodger was soon again implicated in alleged crimes against the state, this time in the agents-provocateurs stage-managed Radical Rising in April 1820 that would lead to the skirmish at Bonnymuir and executions of Andrew Hardie and John Baird at Stirling.

Rodger was accused of being party to the writing of a ‘treasonable address’ – posted on the streets of Glasgow on April 1 1820 and plotting the overthrow of the British state in order to install a provisional government in Scotland. Alarm spread through the streets as banks were surrounded by soldiers. Military and militia forces mustered on Glasgow Green – preparing for an onslaught of Radical hordes from south of the Clyde – while a revolutionary French army was suspected to be encamped on Cathkin Braes.

As the revolution failed to manifest itself, and despite the ‘treasonable address’ being roundly regarded as a hoax, Rodger would spend eleven days in jail where his defiant Radical songs reportedly rang out to such an extent that he was removed to the farthest cell at the back of the prison. It was here on his cell wall he would pencil his ‘Lines Written in a Certain Bridewell by a State Prisoner’:

‘The joys o hame – my bairns, my wife;

Whilst they sit round a cheerless fire,

And wistfully at her enquire

What makes their father stay sae lang?

And if there’s ony thing gane wrang?

‘But what’s the reason I’m confined?

Nae reason, troth, can be assigned,

Unless it be, I chance to differ

Frae them wha will that I shall suffer,

And that my view o politics

Accord no wi some statesmen’s tricks.’

‘The Spirit of the Union’ case would be the last sedition trial in Scotland before the 1832 Reform Act. In ‘An examination of the trials for sedition which have hitherto occurred in Scotland’, in relation to the charges laid against editor MacLeod, Lord Henry Cockburn comments: ‘The worst thing about these libels was their exaggerated animation of language. Swift, or Cobbett, or Sydney Smith, could have said most of what the prisoner said with tolerable safety, and with greater force. But vulgar reformers, who air their opinions in newspapers or at meetings, especially if they be honest and ardent, generally despise skill.’

Undaunted by his struggles as a polemicist, in 1822 Rodger parodied Sir Walter Scott’s obsequious ode ‘Carle Now the King’s Come’, written in honour of King George IV and his Royal jaunt to Edinburgh. ‘Sawney Now the King’s Come’ was published anonymously in the ‘London Examiner’.

‘Tell him he is great and good

And come o Scottish royal blood

To your hunkers lick his fud

Sawney now the King’s come’

It was said that Scott made every effort possible to discover the author.

Rodger continued with his political writings as editor of the ‘Glasgow Reformer’. He contributed songs and verse to the popular collection ‘Whistlebinkie; Songs for the social circle’.

The popularity of Rodgers’ poems and songs led to a subscription being raised to publish a collection of his works under the guise of his humorous pseudonyms: ‘Stray Leaves from the Portfolios of Alisander the Seer, Andrew Whaup, and Humphrey Henceckle’. His work was also published in ‘Poems and songs, humorous, serious and satirical’.

In a parody of popular song ‘The Reel o Bogie’, Rodger satirises the Evangelical ministers caught up in the Church of Scotland’s 10 years conflict which would lead the Disruption of 1843 and establishment of the Free Kirk.

- Author:

- Alexander Rodger (1748-1846)

- Publication Date:

- 1838

- Imprentit:

Edinburgh

‘The Reel o’ Bogie’

Sae meikle Smeddum’s in your heel,

Nae yirthly weight can clog ye –

Not even Nick can damp your zeal

While at your ‘Reel o’ Bogie’Frae ‘The Reel o’ Bogie