The late 16th-century hantle o sindry verse, the Maitland Quarto manuscript, is a gey significant quair o Early Modern Scots poetry. Hooivver, it is faur mair nor jist thon. It is a truly byordinar manuscript on twa groonds: ane, fur its monie rich connections wi wimmen and, twa, fur its inclusion o ane o the earliest ayebidin instances o female homoerotic poetry in Renaissance Europe, in onie leid.

At a time whan scrievin and furthsettin were maistly the preserve o men, and afore onie mensefu notion o wimmen’s – no tae mention gay – equality, richts and representation, the ferlie o the Maitland Quarto manuscript in general, and o Poem 49 in particular, can haurdly be owerthreapit.

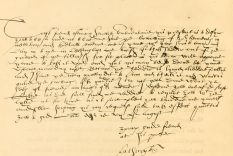

The manuscript wis pit thegither inby the circle o the politically weel-forrit East Lothian faimily o the Maitlands o Lethington. It is linkit chiefly wi Sir Richard Maitland (1496-1586) – statesman, judge, makar, privy coonsellor and Keeper o the Great Seal o Scotland unner Mary Queen o Scots – forby wi his dochter, Marie Maitland (d.1596). Sir Richard dreed gey trauchlesome eesicht, which eventually gart him gae blindt, and Marie is unnerstuid tae hae actit as his literary secreterar. It is widely acceptit that the manuscript wis transcribit and pit thegither by Marie, whase name kythes twice on the title page alang wi the date 1586.

Sir Richard Maitland deed in thon year, and it appears that manuscript wis intendit maistly as a faimily tent-takkin and celebration o his life and literary wark. It opens wi ae dedicatory poem tae Sir Richard and closes wi a wheen elegies and epitaphs; in atween – alang wi a hantle ither scrievins – is the maist complete collection o his poetry that has cam doon tae us.

The manuscript records 95 poems awthegither. Forby those by Sir Richard (43), the attributit poems feature ane by his son John Maitland (whae haudit significant positions, includin Lord Chancellor, unner King James VI) alang wi poems by ither contemporary figures whae were also faimily associates, includin Alexander Montgomerie and King James VI hissel. Monie o the poems contain reflections on the gowsterous political and religious threapins that fasht 16th-century Scotland, while ithers engage wi moral and romantic themes.

Hooivver, aiblins the maist byordinar – yet tae date unnersung – poem in the quair is anonymous; as are aroond ae third o the poems. It is a gey early exemple o Sapphic verse, fur which there is wechtie evidence no jist fur female scrievership, but fur the scrievership o Marie Maitand hersel: Poem 49.

Lear mair aboot The Maitland Quarto and Poem 49

The anonymous, nine-stanza, female-voicit poem o 72 lines taks the traditions o idealisit male freenship and idealisit heterosexual mairriage and glegly subverts them fur tae uphaud lesbian luve. In this, it is doubly gallus: faur fae jist heizin the bond atween twa wimmen raither nor thon atween twa men, it does sae in a wey that is intensely homoerotic raither nor simply platonic.

The initial stanzas o the poem are devotit tae the unbridilit ruise and adoration o the wumman bein addressit. Her ‘splendour […] dois onlie pas all feminine [surpasses thon o aw wimmenkind]’, and the poet descrieves hoo her spirit is filled wi ‘sa greit joy’ as she contemplates her ‘perfectioun’. The poem gangs on:

3e weild me holie at 3our will [Ye govern me halely at yer will]

and raviss [ravish] my affectioun

3our perles vertew dois provoike

and loving kyndnes so dois move

My Mynd to freindschip reciproc

Although the wumman’s ‘perles vertew [peerless virtue]’ and ‘loving kyndness’ are descrievit as movin the poet’s mind tae ‘freindschip reciproc [mutual freenship]’, the erotically-chairgit language strangly mynts at a passion mair sexual nor platonic. The references tae ‘ravishin ma affection’ and the wumman wieldin her ‘halely at her will’ would hae been as loadit wi sexual myntins in the 16th-century as they are whan read the day.

In stanzas 4 and 5, the poet sets oot a series o ‘auntient heroicis [ancient heroes]’ whase faur-kent luve blaikens intae nocht comparit wi her devotion tae the springheid o her amour.

In amitie, Perithous

To Theseus was not so traist [faithfu/leal]

Nor Till Achilles Patroclus

nor Pilades to trew Orest

Not 3it Achates luif so lest [ayebidin]

to gud Enee nor sic freindschip

Dauid to Ionathan profest

nor Titus trew to kynd Iosip

Nor 3it Penelope I wiss [doot/advise]

so luiffed Vlisses in hir dayis

Nor Ruth the kynd moabitiss [Moabitess]

Nohemie as the scripture sayis

nor Portia quhais worthie prayiss [whase worthy praise]

In romaine historeis we reid

Quha did devoir the fyrie brayiss [devour the fiery coals]

To follow Brutus to the deid

Although the citin o a catalogue o kenspeckle companions (biblical, classical and mythological) wis a weel-estaiblishit trope in Renaissance rhetoric on male freenship, oor poet manipulates, in a radical yet cannie mainner, the ideals o male-centric freenship and heterosexual mairriage fur tae forder lesbian luve.

The poet first heizes their female luve abuin thon which existit atween the maist celebratit male freens o lear (whaurby ‘freens’ should aiblins be in invertit commas, fur these relationships were, it is warth takkin tent o, thaimsels loadit wi homoeroticism).

Syne the poet gangs faurer, descrievin renownit exemplars o husband-wife pairins whase luve is siblike owergaen by thon which exists atween her and her beluvit; it is mair michty nor thon o Penelope, whae ‘so luiffed vlisses in hir dayis’, and thon o Portia ‘quha did devoir the fyrie brayiss/To follow brutus to the deid’.

Unco kenably, the poet includes in this stanza on idealisit mairriage a female couple: Ruth and Naomi, invokin fur the reader – ‘as the scripture sayis’ – Ruth’s hecht o ayebidin lealtie, wumman tae wumman, in the Auld Testament. [‘And Ruth seyed, Dinna entreat me tae lea thou, or tae haud aff fae follaen efter thou; fur whaur thou gangs, A wull gang, and whaur thou bides, A wull bide tae; yer ain kinsfowk wull be ma kinsfowk and yer God ma ain God. Whaur thou dees, wull A dee, and there wull A be yirdit. Micht the Lord dae thon untae masel and mair forby gin aucht but deith thou and me pairt’, The Buik o Ruth 1:16–17, author’s ain owersettin fae the 1560 Geneva Bible].

The poet sicweys situates the bond atween the twa quines baith inby and ootwi the spheres o male freenship and heterosexual mairriage. Their luve mells, souders and, abuin aw, transcends thon paulie caitegories in a wey comparable aiblins alane tae the bond atween Ruth and Naomi; whae, significantly, are evokit in the context o perfit mairriage. It is a liminal luve, which, in the poet’s wirds, truth shall pruive ‘sa far above’ and ‘mair holie and religious’ nor onie ither:

treuth sail try sa far above

The auntient heroicis love

as salbe thocht prodigious

and plaine experience sail prove

Mair holie and religious

It is in the sixth stanza, hooivver, that the poem raxes its – unjoukably sexual – heid-hicht:

Wald michtie Joue [Jupiter] grant me the hap [fortune]

With 3ow to haue [hae] 3our Brutus pairt

and metamorphosing our schap

My sex intill his vaill convert

No Brutus then sould caus ws smart [hurt]

as we doe now, vnhappie wemen

Then sould we bayth with joyfull hairt

honour and blis [bless] the band of hymen

Here, wi echoes o the myth o Iphis and Ianthe in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (whaur Iphis is transformit intae a man fur tae mairry the lass, Ianthe, that she luves), the author richt oot states her desire tae metamorphose intae a man fur that the twa wimmen micht mairry: syne the ‘unhappie wemen’ would ‘smart [hurt]’ nae langer, but ‘wi ‘joyfull hairt/honour and blis [bless] the band of hymen [Hymen = the Greek god o mairriage]’.

In this, the poem is byous gallus and faur aheid o its time in gien explicit and hertfelt voice tae lesbian luve – tae an impassionit desire fur legally unjoukable and bindin mairriage atween twa wimmen. At the ae time, hooivver, it is aye thirlt tae the strictures o 16th-century norms in conceivin o a realisable and permissible relationship anely in terms o mairriage atween a man and a wumman.

The poet wishes tae hae the ‘pairt’ o the wumman’s ‘Brutus [husband]’ and fur her ‘sex’ tae be convertit intae ‘his vaill [veil]’ fur that they micht leafully mairry – forby consummate their mairriage. It is interestin tae note that, although ‘pairt’ could be read simply as ‘pairt’ or ‘role’, anither definition as listit in ‘A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (up to 1700)’ is: ‘a pairt, memmer or organ o a human or animal body’, includin ‘penis’. (It is aiblins warth takkin tent o the fack that this double meanin is present in ither European languages forby: fur exemple, the German wird fur ‘pairt’ (Teil) can mean ‘penis’ in a colloquial context; which is pleyed on, fur exemple, in the Rammstein sang, ‘Mein Teil’).

Yet – there is nae sense that the poet actually wishes tae be a man. Raither, she is a wumman warkin inby the smuirin doonhauds o 16th-century heteronormative society, whaur anely a laddie’s kythe micht allou fur her mairryin her jo.

The follaen stanza bigs on the theme o the uniqueness o their luve, unnerlinin hoo, gin their marital union could be realisit, their ‘‘mair perfyte amitie [mair perfit amity]’ would ootdae thon o onie faur-kent pair oot-through history and ‘mair worthie recompence sould merit’.

3ea certainlie we sould efface

Pollux and Castoris memorie

and gif that thay desseruit place [gin they deservit place]

amang the starris for loyaltie

Then our mair perfyte amitie

mair worthie recompence sould merit

Syne the twa stanzas at the hinder end represent a shift, acceptin, awbeit wi dowie hert, the doonhauds smuirt on their luve by ‘nature’ – their female sex – and ‘hymen’ – the institution o mairriage, which doesnae permit union atween wimmen.

Freenship is the anely option open tae them, and sae tae thon ‘freindschip and amitie sa suire’ they will gie themsels, wi nae haudin aff, wi ‘sa greit feruencie and force’ that ‘not bot deid sall ws divorce’ – bringin tae mind aince mair no jist Ruth’s wirds tae Naomi in the Auld Testament (‘gin aucht but deith thou and me pairt’) but, o coorse, the commitment o mairriage.

The final stanza ends the poem in siblike vein, heizin their female freenship abuin onie male freenship that has ivver existit: nae ‘erthlie thing’ shall ‘disseuer [sinder]’ it, and its ‘constancie’ will mak siccar that they bide ‘in perfyte amitie for euer [in perfit amity fur ivver]’. Hooivver, the lamentation o the fack that ‘‘aduersitie ws vex [adversity fashes us]’ forby the intense passion gien voice in the foregane verses leas it in nae doot that mair will aye be desirit.

And thocht [though] aduersitie ws vex

3it be [by] our freindschip salbe sein [shall be seen]

Thair is mair constancie in our sex

Then euer amang men hes bein

no troubill, torment, greif, or tein [sufferin/dree]

nor erthlie thing sall ws disseuer

Sic constancie sall ws mantein

In perfyte amitie for euer.

Finis.

Poem 49 is a pooerfu voice-gien, in Scots, o female same-sex desire. Although its hert-stappin hecht o lesbian devotion ultimately defers tae the sair fecht o the smuirin heteronormative doonhauds o 16th-century Scotland, its gallus passion and byous bonnie lines aye gar the hert greet mair nor 400 year later – and the poem bides faur aheid o its time forby gey ferlie.

Scrievership

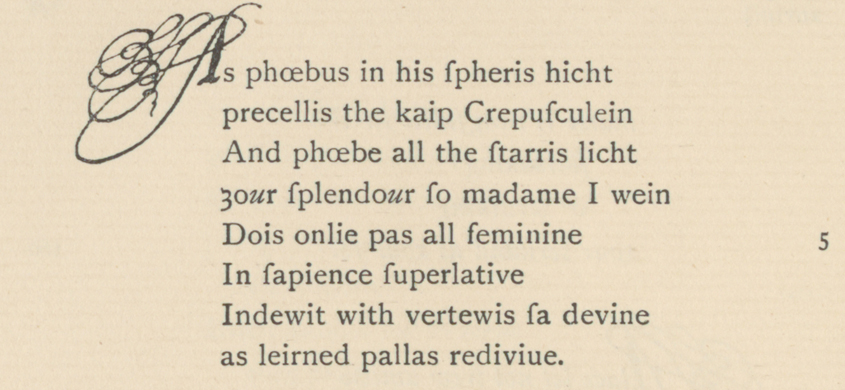

The poem is unjoukably scrievit in the voice o a wumman and addressit tae anither wumman. The first stanza maks clear the female sex o the bodie bein addressit – ‘Your splendour so madame I wein / dois onlie pas all feminine [wimmenkind]’ – forby its female voice is gart explicit at sindry pynts elsewhaur in the poem: ‘As we doe now vnhappie wemen’; ‘Thair is mair constancie in our sex / Then euer amang men hes bein’; ‘My [female] sex intill his vaill convert’.

Forby, monie ither factors support the poem’s female scrievership. First, the poem is anonymous and kythes uniquely in this ae faimily manuscript. Baith o thon factors support female scrievership in this era; tae pit it simply, men had nae reason no tae pit their name tae their scrievin or tae limit its circulation. Mairower, there is siblike evidence fae elsewhaur in the Renaissance era o wimmen furthsettin their wark in hidlins through the anonymous inclusion o their poetry in manuscript miscellanies.

Saicont, sindry internal textual factors speik tae a genuine female voice, sic as the celebration o female constancy in the final stanza: ‘Thair is mair constancie in our sex / Then euer amang men hes bein’. Although the fordels o male freenship had lang been eulogisit, wimmen in the 16th-century were thocht tae be emotionally inferior and sicweys incapable o formin mensefu freenships in the ae wey as men. Syne these lines can be read as a proto-feminist repone tae this deep-rootit wimmen-laithin notion, wi the smeddumfou championin o ‘our sex’ reflectin a strang sense o female identity.

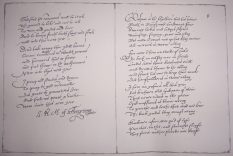

Third, sindry ither o the anonymous poems in the manuscript also speik tae female experience in life and luve. Fur exemple, there is ae poem (66) on marital cruelty at the hauns o a husband forby twa ither potentially Sapphic – awbeit mair subtle nor Poem 49 – poems (38 and 72), while ithers yet mak mention o wimmen as buik owners and as makars in their ain richt. As wi Poem 49, their female themes thegither wi their anonymity and unique kythin in the Maitland Quarto manuscript speik fur female scrievership. Indeed, the female-voicit Poem 66 is semi-anonymously signit wi the initials ‘G.H.’, which hae been strangly identifiet wi Grizel Hay o Yester (born efter 1560); dochter o William Hay, Fifth Lord Hay o Yester, whase faimily wis connectit tae the launs o Lethington.

Taen thegither, we micht jalouse, awbeit cannily, the existence o a community o wimmen makars: we micht jalouse Marie Maitland, the maist likely compiler o the manuscript, at the hert o a group o wimmen joukin the patriarchal doonhauds o Early Modern Scottish society and slippin their poetry in hidlins intae a faimily manuscript. This brings us tae the fourth threap in favour o female scrievership o Poem 49; namely, that we hae in Marie Maitland a byous strang candidate fur its author.

Marie Maitland wis dootless a weel-leared and literate wumman, and awmaist siccarly the bodie whae transcribit and pit thegither the manuscript. Significantly, ither o the anonymous poems in the manuscript (aiblins scrievit by ither wimmen in the group?) mynt at her role in pittin thegither the manuscript and, mairower, explicitly celebrate her ain scrieverly talents forby.

In ae poem (85), she is comparit directly wi ither female poets, includin the historical Greek poet Sappho o Lesbos – famous as a wumman makar forby (in)famous fur her romantic fankles wi ither wimmen, as reflectit in her poetry. Indeed, we can speir oot the roots o the wirds ‘Sapphic’ and ‘lesbian’ (o Lesbos) back tae her. Poem 85 names ‘Maistres Marie’ ootricht, associates her wi ‘sapho saige’ and her ‘saphic songe’, and states that Marie ‘a plesant poet perfyte sall […] be’ whan ‘this buik’ is feenisht: a skyrie reference, it seems, tae Marie’s twafauld function as baith compiler o the manuscript and a poet in her ain richt – ane in the image o Sappho.

Gin there is a rowth o evidence fur female scrievership, syne there is muckle evidence forby tae suggest that we need luik nae faurer nor Marie Maitland fur oor 16th-century Scottish Sappho. Syne aw in aw, Poem 49 is ayont byordinar: as muckle fur its gallus female scrievership in a warld smuirt by patriarchy as fur its pooerfu uphaudin o intense lesbian luve in a society whaur heterosexual union wis the anely form permittit.

Language

The poem is scrievit in Early Modern Scots. It shaws Scots grammatical merkers sic as the ‘-t / -it’ endin on weak verbs that we aye see in Modern Scots verbs – fur exemple, indewit (Modern English: endowed; Modern Scots: endowit); profest (professed; professit); desseruit (deserved; deservit). Forby we see the noo historical Scots ‘-is’ inflection fur tae merk possessives and plurals, as in spheris (sphere’s); vertewis (virtues); dayis (days); and goddis (gods). We also see the gey kenable Aulder Scots merker o ‘quh-’ at the stert o wirds that noo stert wi ‘wh-’: as in, fur exemple, quhais (whose); quha (who); and quhilk (which).

The fricative soond ‘-ch’, aye present in Modern Scots, is seen representit in wirds sic as ‘licht’, ‘hicht’, ‘thocht’ and ‘michtie’. The leid-kist o the poem is forby fou o wirds that we aye ken in Modern Scots the day, awbeit whiles in aulder forms o spellin, fae ‘amang’, ‘mair’ and ‘hairt’ tae ‘sic’, ‘pairt’ and ‘bayth (baith)’. On the ither haun, ither items in the Scots leid-kist o the 16th-century poem arenae in iveryday yaisage the day; fur exemple, the verb ‘tae wein’ meanin ‘tae jalouse, think, doot, believe’; the adjective ‘traist’ meanin ‘leal, faithfu, trustwirthy, reliable’, and the noun ‘tein’ meanin ‘sufferin, dree, trauchle’. Forby the Scots o the poem shaws the noo obsolete ȝ (yogh ) as representin ‘y’ (3our – your; 3it – yet) and, less aft, ‘th’ (3airtill – thereto; 3e – the). We also see ‘v’ and ‘u’ yaisit interchyngably (vnknawin; prove; vnhappie; deseruit; feruencie; ws; aduersitie; euer).

LGBT+ Bygane Month

Gin the existence and warth o the Scots language oot-through Scotland’s history is oft owerlookit and broukit, syne thon o Scotland’s wimmen – no tae mention queer wimmen – tholes the same dree forby. This Wee Windae is anent a byordinar 16th-century Sapphic poem in Early Modern Scots. Furthset in LGBT History Month Februar 2021, it aims tae leam a skyrie licht on and celebrate the true rowth o Scotland’s bygane in aw its diversity.

The late 16th-century verse miscellany, the Maitland Quarto manuscript, is a highly significant collection of Early Modern Scots poetry. However, it is far more than just that. It is a truly remarkable manuscript on two counts: one, for its multiple rich connections with women and, two, for its inclusion of one of the earliest surviving instances of female homoerotic poetry in Renaissance Europe, in any language.

At a time when writing and publishing were largely the preserve of men, and before any meaningful notion of women’s – let alone gay – equality, rights and representation, the significance of the Maitland Quarto manuscript in general, and of Poem 49 in particular, can scarcely be overstated.

The manuscript was composed within the circle of the politically prominent East Lothian family of the Maitlands of Lethington. It is associated in particular with Sir Richard Maitland (1496-1586) – statesman, judge, poet, privy counsellor and Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland under Mary Queen of Scots – and with his daughter, Marie Maitland (d.1596). Sir Richard suffered from very poor eyesight, which eventually resulted in his turning blind, and Marie is understood to have acted as his literary secretary. It is widely accepted that the manuscript was transcribed and compiled by Marie, whose name appears twice on the title page along with the date 1586.

Sir Richard Maitland died in that year, and it appears that the manuscript was intended primarily as a family commemoration and celebration of his life and literary accomplishments. It opens with a single dedicatory poem to Sir Richard and closes with a series of elegies and epitaphs; in between – along with a miscellany of other works – is the most complete collection of his poetry that has come down to us.

The manuscript records 95 poems in total. As well as those by Sir Richard (43), the attributed poems feature one by his son John Maitland (who held significant positions, including Lord Chancellor, under King James VI) along with poems by other contemporary figures who were also family associates, including Alexander Montgomerie and King James VI himself. Many of the poems contain reflections on the turbulent political and religious climate of 16th-century Scotland, while others engage with moral and romantic themes.

However, perhaps the most remarkable – yet to date undersung – poem in the manuscript is anonymous; as around one third of the poems are. It is a notably early example of Sapphic verse, for which there is compelling evidence not only of female authorship, but of the authorship of Marie Maitland herself: Poem 49.

Learn more about The Maitland Quarto and Poem 49

The anonymous, nine-stanza, female-voiced poem of 72 lines takes the traditions of idealised male friendship and idealised heterosexual marriage and deftly subverts them to articulate lesbian love. In this, it is doubly radical; not only does it extol the bond between two women rather than two men, but it does so in a way that is intensely homoerotic rather than simply platonic.

The initial stanzas of the poem are devoted to the unbridled praise and adoration of the woman being addressed. Her ‘splendour […] dois onlie pas all feminine [surpasses that of all womankind]’, and the poet describes how her spirit is filled with ‘sa greit joy’ as she contemplates her ‘perfectioun’. The poem goes on:

3e weild me holie at 3our will [Ye govern me wholly at your will]

and raviss [ravish] my affectioun

3our perles vertew dois provoike

and loving kyndnes so dois move

My Mynd to freindschip reciproc

Although the woman’s ‘perles vertew [peerless virtue]’ and ‘loving kyndness’ are described as moving the poet’s mind to ‘freindschip reciproc [mutual friendship]’, the erotically-charged language strongly suggests a passion more sexual than platonic. The references to ‘ravishing my affection’ and the woman wielding her ‘wholly at her will’ would have been as loaded with sexual connotations in the 16th-century as they are when read today.

In stanzas 4 and 5, the poet lists a series of ‘auntient heroicis [ancient heroes]’ whose famed love pales into insignificance compared with her devotion to the object of her adoration.

In amitie, Perithous

To Theseus was not so traist [faithful]

Nor Till Achilles Patroclus

nor Pilades to trew Orest

Not 3it Achates luif so lest [lasting]

to gud Enee nor sic freindschip

Dauid to Ionathan profest

nor Titus trew to kynd Iosip

Nor 3it Penelope I wiss [advise/believe]

so luiffed Vlisses in hir dayis

Nor Ruth the kynd moabitiss [Moabitess]

Nohemie as the scripture sayis

nor Portia quhais worthie prayiss [whose worthy praise]

In romaine historeis we reid

Quha did devoir the fyrie brayiss [devour the fiery coals]

To follow Brutus to the deid

Although the citing of a catalogue of famous companions (biblical, classical and mythological) was a well-established trope in Renaissance rhetoric on male friendship, our poet radically yet subtly manipulates the ideals of male-centric friendship and heterosexual marriage to exalt lesbian love.

The poet first elevates their female love above that which existed between the most celebrated male friends of lore (whereby ‘friends’ should perhaps be in inverted commas, as these relationships were, it is worth noting, themselves charged with homoerotic undertones).

The poet then goes further, describing renowned exemplars of husband-wife pairings whose love is likewise eclipsed by that which exists between her and her beloved; it is greater than that of Penelope, who ‘so luiffed vlisses in hir dayis’ and that of Portia ‘quha did devoir the fyrie brayiss/To follow brutus to the deid’.

Strikingly, the poet includes in this stanza on idealised marriage a female couple: Ruth and Naomi, invoking for the reader – ‘as the scripture sayis’ – Ruth’s promise of ever-lasting fidelity, woman to woman, in the Old Testament. [‘And Ruth answered, Intreat me not to leaue thee, nor to departe from thee; for whither thou goest, I wil goe: and where thou dwellest, I wil dwell: thy people shalbe my people, and thy God my God. Where thou dyest, wil I dye, and there wil I be buryed. The Lord do so to me & more also, if oght but death departe thee & me’, The Book of Ruth 1:16-17, 1560 Geneva Bible].

Thus the poet situates the bond between her and the object of her affections both within and outwith the spheres of male friendship and heterosexual marriage. Their love blurs, combines and, ultimately, transcends these unsatisfactory categories in a way comparable perhaps only to the bond between Ruth and Naomi; who, significantly, are evoked in the context of exemplary marriage. It is a liminal love, which, in the poet’s words, truth shall prove ‘sa far above’ and ‘mair holie and religious’ than any other:

treuth sail try sa far above

The auntient heroicis love

as salbe thocht prodigious

and plaine experience sail prove

Mair holie and religious

It is in the sixth stanza, however, that the poem reaches its – explicitly sexual – climax:

Wald michtie Joue [Jupiter] grant me the hap [fortune]

With 3ow to haue [have] 3our Brutus pairt

and metamorphosing our schap

My sex intill his vaill convert

No Brutus then sould caus ws smart [hurt]

as we doe now, vnhappie wemen

Then sould we bayth with joyfull hairt

honour and blis [bless] the band of hymen

Here, with echoes of the myth of Iphis and Ianthe in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (in which Iphis is transformed into a man in order to marry the girl, Ianthe, that she loves), the author states unequivocally her desire to metamorphose into a man in order that the two women may be married: the ‘unhappie wemen’ would then no longer ‘smart [hurt]’ but ‘with ‘joyfull hairt/honour and blis [bless] the band of hymen [Hymen = the Greek god of marriage]’.

In this, the poem is wildly ahead of its time in giving explicit and heartfelt voice to lesbian love – to an impassioned desire for legally valid and binding marriage between two women. At the same time, however, it remains thirled to the strictures of 16th-century norms in conceiving of a realisable and permissible relationship only in terms of marriage between a man and a woman.

The poet wishes to have the ‘pairt [part]’ of the woman’s ‘Brutus [husband]’ and for her ‘sex’ to be converted into ‘his vaill [veil]’ in order that they may legitimately marry – and consummate their marriage. Interestingly, although ‘pairt’ could be read simply as ‘part’ or ‘role’, another definition as listed in ‘A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue (up to 1700)’ is: ‘a part, member or organ of a human or animal body’, including ‘penis’. (It is perhaps worth noting that this double meaning is also present in other European languages: for example, the German word for ‘part’ (Teil) can also mean ‘penis’ in a colloquial context; which is played on, for example, in the Rammstein song, ‘Mein Teil’).

Yet – there is no sense that the poet actually wishes to be a man. Rather, she is a woman working within the confines of 16th-century heteronormative society, where assuming the veil of a male body appears to be the only way to legitimately marry the woman she loves.

The following stanza builds on the theme of the unique incomparability of their love, stressing how, if their marital union could be realised, their ‘mair perfyte amitie [more perfect amity]’ would eclipse that of any famed pair throughout history and ‘mair worthie recompence sould merit’.

3ea certainlie we sould efface

Pollux and Castoris memorie

and gif that thay desseruit place [if they deserved place]

amang the starris for loyaltie

Then our mair perfyte amitie

mair worthie recompence sould merit

The final two stanzas then represent a shift, accepting, albeit resignedly, the limitations imposed on their love by ‘nature’ – their female sex – and ‘hymen’ – the institution of marriage, which does not permit union between women.

And as we ar thocht [though] till our wo [woe]

nature and fortoun doe conjure [conspire]

and hymen also be our fo

3it luif of vertew [yet love of virtue] dois procuire

freindschip and amitie sa suire [so sure]

with sa greit feruencie and force [such great fervency and force]

Sa constantlie quhilk sall induire [which shall endure so constantly]

That not bot deid sall ws divorce

Friendship is the only option open to them, and so to that ‘freindschip and amitie sa suire’ they will devote themselves unreservedly, with ‘sa greit feruencie and force’ that ‘not bot deid sall ws divorce’ – evocative not only, once again, of Ruth’s words to Naomi in the Old Testament (‘if ought but death depart thee and me’) but, of course, the commitment of marriage.

The final stanza ends the poem in similar vein, elevating their female friendship above any male friendship that has ever existed: no ‘erthlie thing’ shall ‘disseuer [sever]’ it, and its ‘constancie’ will ensure that they remain ‘in perfyte amitie for euer [in perfect amity for ever]’. However, the lamentation of the fact that ‘aduersitie ws vex [adversity vexes us]’ along with the intense passion articulated in the preceding verses leave it in no doubt that more will always be desired.

And thocht [though] aduersitie ws vex

3it be [by] our freindschip salbe sein [shall be seen]

Thair is mair constancie in our sex

Then euer amang men hes bein

no troubill, torment, greif, or tein [suffering/sorrow]

nor erthlie thing sall ws disseuer

Sic constancie sall ws mantein

In perfyte amitie for euer.

Finis.

Poem 49 is a powerful articulation, in Scots, of female same-sex desire. Although its breathtaking declaration of lesbian devotion ultimately defers to the heteronormative limitations of 16th-century Scotland, its heartfelt passion and beautiful lines still move more than 400 years later – and the poem remains as radical as it is rare.

Authorship

The poem is unambiguously written in the voice of a woman and addressed to another woman. The first stanza makes clear the female sex of the person being addressed – ‘Your splendour so madame I wein / dois onlie pas all feminine [womankind]’ – and its female voice is made explicit at various points elsewhere in the poem: ‘As we doe now vnhappie wemen’; ‘Thair is mair constancie in our sex / Then euer amang men hes bein’; ‘My [female] sex intill his vaill convert’.

Moreover, many other factors also support the poem’s female authorship. First, the poem is anonymous and occurs uniquely in this single family manuscript. Both of these factors support female authorship in this era; quite simply, men had no reason not to put their name to their writing or to limit its circulation. Further, there is comparable evidence from elsewhere in the Renaissance era of women covertly publishing through the anonymous inclusion of their poetry in manuscript miscellanies.

Second, numerous internal textual factors speak to a genuine female voice, such as the celebration of female constancy in the final stanza: ‘Thair is mair constancie in our sex / Then euer amang men hes bein’. Although the virtues of male friendship had long been eulogised, women in the 16th-century were believed to be emotionally inferior and thus incapable of forming meaningful friendships in the same way as men. These lines can therefore be read as a proto-feminist repudiation of this deep-rooted misogynistic notion, with the spirited championing of ‘our sex’ reflecting a strong sense of female identity.

Third, various other of the anonymous poems in the manuscript also speak to female experience in life and love. For example, there is a poem (66) on marital cruelty at the hands of a husband as well as two other potentially Sapphic – albeit more subtle than Poem 49 – poems (38 and 72), while others still allude to women as book owners and creative agents. As with Poem 49, their female themes together with their anonymity and unique appearance in the Maitland Quarto manuscript speak for female authorship. Indeed, the female-voiced Poem 66 is semi-anonymously signed with the initials ‘G.H.’, which have been strongly identified with Grizel Hay of Yester (born after 1560); daughter of William Hay, Fifth Lord Hay of Yester, whose family was connected to the lands of Lethington.

Taken together, this all points tantalisingly towards the potential existence of a community of women poets: to Marie Maitland, the likely compiler of the manuscript, as the centre of a group of women subverting the patriarchal conventions of Early Modern Scottish society and covertly slipping their poetry into a family manuscript. This brings us to the fourth argument in favour of female authorship of Poem 49; namely, that we have in Marie Maitland a remarkably strong candidate for its author.

Marie Maitland was clearly a highly educated and literate woman, and almost certainly the transcriber and compiler of the manuscript. Significantly, other of the anonymous poems in the manuscript (perhaps written by other women in the group?) not only allude to her role in compiling the manuscript but explicitly celebrate her own poetic talents.

In one poem (85), she is compared directly to other female poets, including the historical Greek poet Sappho of Lesbos – famous as a woman poet and (in)famous for her romantic entanglements with other women, as reflected in her poetry. Indeed, we can trace the roots of the words ‘Sapphic’ and ‘lesbian’ (of Lesbos) back to her. Poem 85 explicitly names ‘Maistres Marie’, associates her with ‘sapho saige’ and her ‘saphic songe’, and states that Marie ‘a plesant poet perfyte sall […] be’ when ‘this buik’ is finished: a clear reference, it would appear, to Marie’s dual function as both compiler of the manuscript and a poet in her own right – one in the image of Sappho.

If there is an abundance of evidence for female authorship, there is therefore also compelling evidence to suggest that we need look no further than Marie Maitland for our 16th-century Scottish Sappho. All in all, then, Poem 49 emerges as remarkable both for its female authorship in a suffocatingly male-dominated world, and for its powerful articulation of intense lesbian love in a society in which heterosexual union was the only form permitted.

Language

The poem is written in Early Modern Scots. It exhibits Scots grammatical markers such as the ‘-t / -it’ ending on weak verbs that we still see in Modern Scots verbs – for example, indewit (Modern English: endowed; Modern Scots: endowit); profest (professed; professit); desseruit (deserved; deservit). There is also the now historical Scots ‘-is’ inflection to mark possessives and plurals, as in spheris (sphere’s); vertewis (virtues); dayis (days); and goddis (gods). Similarly, we see the striking Older Scots marker of ‘quh-’ at the beginning of words that now start with ‘wh-’: as in, for example, quhais (whose); quha (who); and quhilk (which).

The fricative sound ‘-ch’, still present in Modern Scots, is seen represented in words such as ‘licht’, ‘hicht’, ‘thocht’ and ‘michtie’. The vocabulary of the poem also contains various words still in common currency in Modern Scots, albeit sometimes in an older form of spelling, from ‘amang’, ‘mair’ and ‘hairt’ to ‘sic’, ‘pairt’ and ‘bayth (baith).’ By contrast, other items of Scots vocabulary in the 16th-century poem have since fallen out of common usage; for example, the verb ‘tae wein’ meaning ‘to surmise, suppose, think, believe’; the adjective ‘traist’ meaning ‘faithful, trustworthy, reliable’, and the noun ‘tein’ meaning ‘suffering, sorrow, affliction’.

The Scots of the poem also exhibits the now obsolete ȝ (yogh ) as representing ‘y’ (3our – your; 3it – yet) and, less frequently, ‘th’ (3airtill – thereto; 3e – the). We also see ‘v’ and ‘u’ used interchangably (vnknawin; prove; vnhappie; deseruit; feruencie; ws; aduersitie; euer).

See the links below for further reading.

LGBT+ History Month

If the existence and worth of the Scots language throughout Scotland’s history is often overlooked and undervalued, so, too, is that of Scotland’s women – let alone queer women. This Wee Windae is about a magnificent 16th-century Sapphic poem in Early Modern Scots. Launched in LGBT History Month February 2021, it aims to shine a light on and celebrate the true richness of Scotland’s past in all its diversity.

- Author:

- Mary Maitland

- Publication Date:

- 1586

- Imprentit:

East Lothian

Poem 49 final stanza

And thocht [though] aduersitie ws vex

3it be [by] our freindschip salbe sein [shall be seen]

Thair is mair constancie in our sex

Then euer amang men hes bein

no troubill, torment, greif, or tein [sufferin/dree]

nor erthlie thing sall ws disseuer

Sic constancie sall ws mantein

In perfyte amitie for euer.